In West Iceland’s Borgarfjörður region, Deildartunguhver releases near-boiling water at a constant rate unmatched anywhere else in Europe. Unlike geysers or eruptive geothermal features, Deildartunguhver is defined by persistence—its steady output supplying heat to nearby towns while revealing the mechanics of Iceland’s geothermal systems without interruption.

The location of Deildartunguhver

Latitude

64.6636

Longitude

-21.4103

Deildartunguhver

Deildartunguhver is located in the Reykholtsdalur valley, north of Borgarnes, where geothermal heat rises through fractured volcanic bedrock. The spring discharges water at a temperature of approximately 97°C, close to boiling at sea level, and with an average flow rate of around 180 litres per second. This combination of temperature and volume makes it the most powerful hot spring in Europe by output.

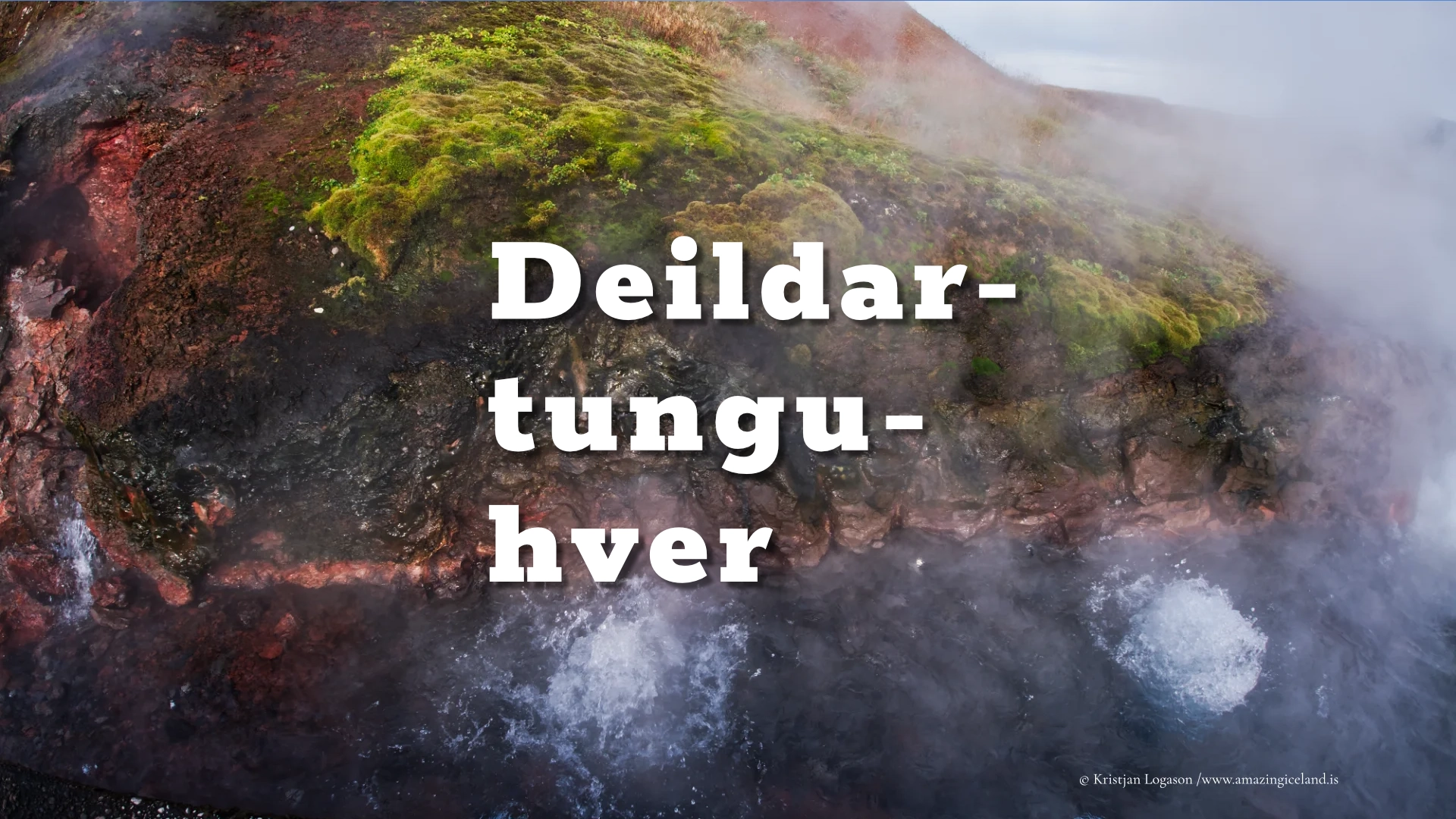

The spring itself is visually restrained. Water emerges from a rocky source area surrounded by steam, mineral deposits, and engineered barriers. There are no eruptions, no rhythmic cycles, and no dramatic jets. Instead, Deildartunguhver expresses geothermal energy as a constant process—continuous heat transfer from depth to surface.

From a geological standpoint, the spring is linked to deep circulation of groundwater heated by geothermal gradients associated with Iceland’s active volcanic zones. Water percolates downward, is heated at depth, and returns rapidly to the surface through permeable fractures. The speed of this circulation prevents significant cooling, preserving the spring’s high temperature.

What distinguishes Deildartunguhver is not only its natural characteristics, but its integration into human infrastructure. Since the mid-20th century, the spring has been harnessed as a primary heat source for district heating systems in Borgarnes, Akranes, and surrounding communities. Insulated pipelines transport hot water over long distances with minimal heat loss.

This use reflects a broader Icelandic approach to geothermal resources: direct utilization rather than extraction for spectacle. Deildartunguhver is not protected from use; it is protected through use. Its management prioritizes sustainability, ensuring that withdrawal rates do not exceed natural recharge.

The site functions as a working case study in renewable energy application. It demonstrates how geothermal systems can be integrated into daily life without altering their fundamental behavior.

The surrounding area reinforces this utilitarian character. Protective railings and controlled access ensure safety, while informational signage focuses on explanation rather than attraction. Visitors observe from a distance, emphasizing that this is not a bathing site or interactive feature.

Vegetation near the spring reflects the microclimate created by constant heat. Mosses and grasses grow year-round in close proximity, while mineral precipitation coats nearby rock surfaces. Steam output varies with air temperature and wind, making the spring more visually prominent in cold conditions.

Unlike geysers that depend on pressure build-up, Deildartunguhver’s steady flow means it is unaffected by short-term variation. This stability makes it particularly valuable for long-term energy planning.

Culturally, Deildartunguhver represents Iceland’s pragmatic relationship with natural forces. The spring is not mythologized to the same extent as eruptive geothermal features. Its value lies in reliability rather than symbolism.

This distinction is important. Deildartunguhver illustrates how geothermal phenomena can be understood as infrastructure rather than spectacle—an everyday presence underpinning settlement and comfort in a subarctic climate.

The spring’s quiet operation contrasts sharply with more famous sites along the Golden Circle, yet its contribution to Icelandic society is arguably greater.

Deildartunguhver ultimately reframes geothermal power. It shows that energy need not announce itself dramatically to be transformative. Heat emerges, is captured, and disappears into pipes—its impact felt far from its source.

Interesting facts:

- Deildartunguhver is Europe’s most powerful hot spring by flow rate.

- Water emerges at approximately 97°C.

- Average discharge is around 180 litres per second.

- The spring supplies district heating to multiple towns in West Iceland.

- It is not suitable for bathing due to extreme temperature.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Steam over water: Focus on vapor movement rather than the source pool.

- Cold conditions: Winter enhances contrast between steam and air.

- Include infrastructure: Pipes and barriers explain purpose and scale.

- Avoid close-ups: Distance reinforces heat and danger.

- Neutral color grading: Preserve mineral tones and steam density.