Situated in North Iceland east of Akureyri, Lake Mývatn is one of the country’s most scientifically significant landscapes. Shallow, nutrient-rich, and surrounded by young volcanic formations, Mývatn supports an ecosystem unparalleled at its latitude while remaining deeply embedded within the active Krafla volcanic system. It is a place where geology is not background context but the primary driver of ecological structure.

The location of Lake Mývatn in North Iceland

Latitude

65.6030

Longitude

-16.9980

Lake Mývatn in North Iceland

Geological origin and volcanic framework

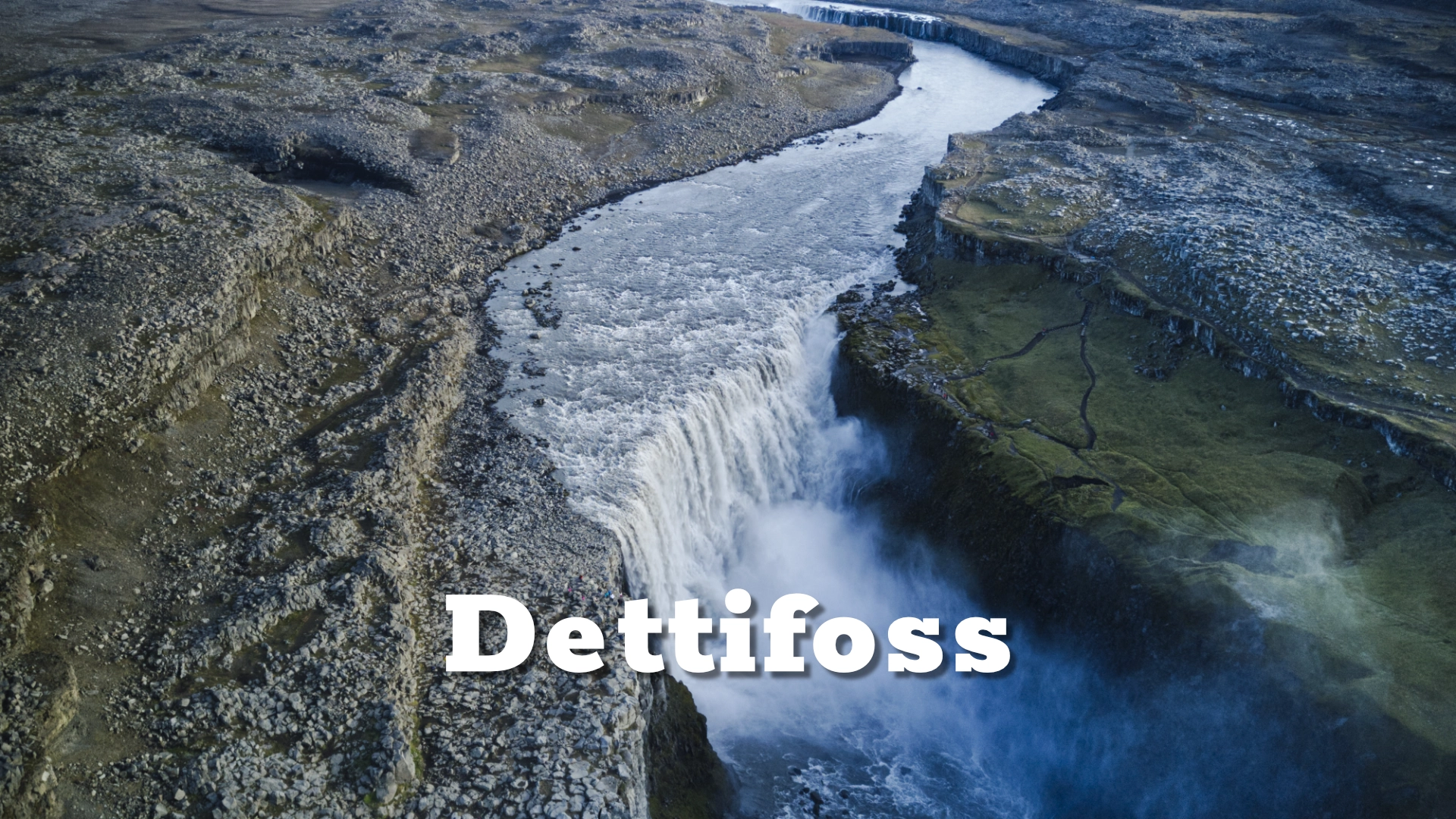

Lake Mývatn owes its existence to basaltic volcanism rather than glacial excavation. Approximately 2,300 years ago, lava flows from eruptions associated with the Krafla volcanic system dammed the drainage of the Laxá River, creating a shallow basin that gradually filled with water. This origin is critical: unlike deep tectonic or glacial lakes, Mývatn is structurally young, shallow, and directly shaped by lava emplacement.

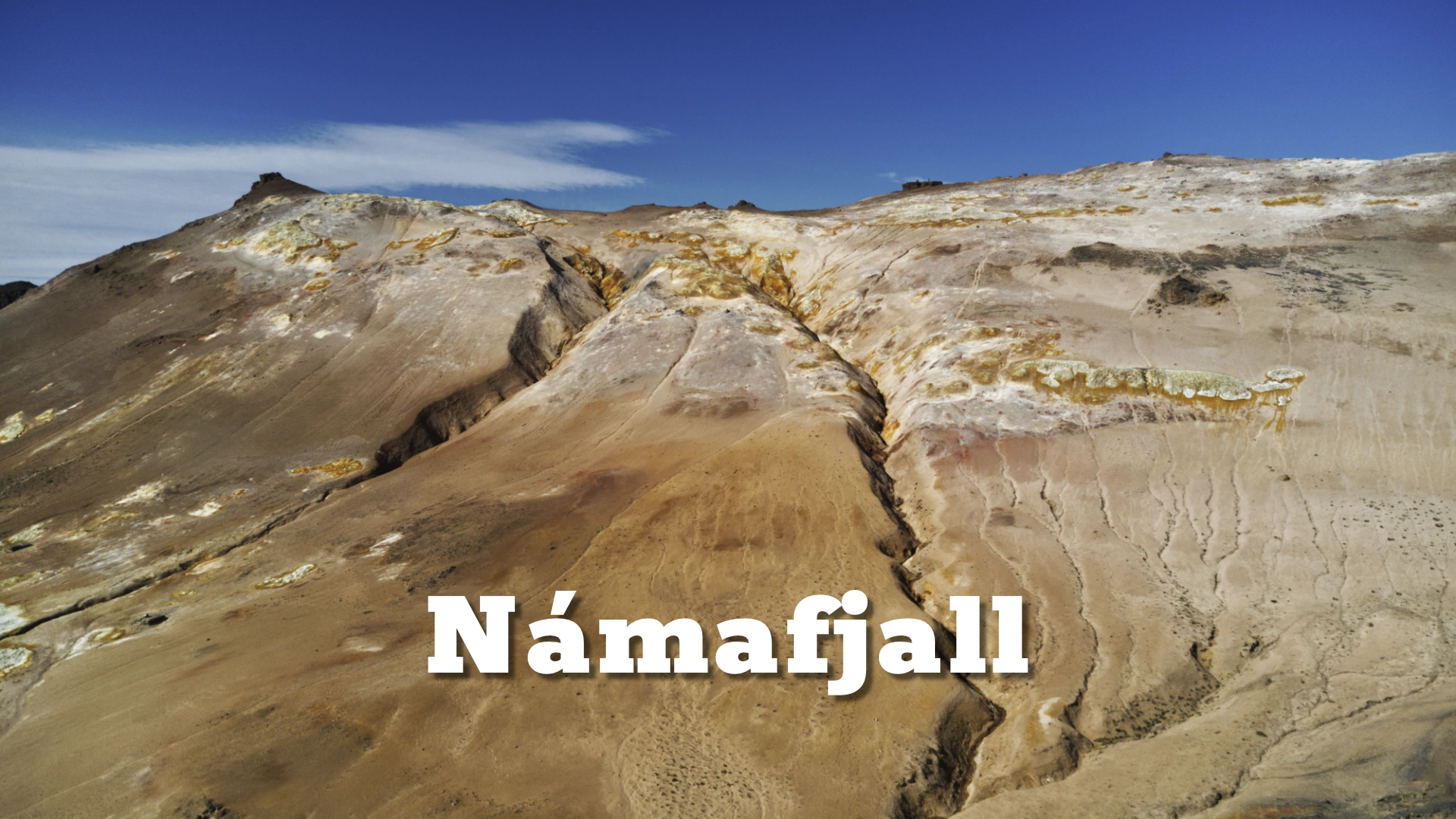

The surrounding landscape is dominated by lava fields, rootless cones, explosion craters, and fissures—features that reflect magma–water interaction rather than sustained central eruptions. The most iconic of these are the pseudocraters at Skútustaðir, formed when lava flowed over wetlands and shallow water, generating steam explosions without a direct magma conduit. These formations are often misidentified as volcanic cones, but their structure records surface-level interaction rather than deep eruptive plumbing.

The proximity of geothermal heat further distinguishes Mývatn. Subsurface temperatures remain elevated across much of the basin, influencing groundwater chemistry, sediment deposition, and seasonal ice formation. In winter, parts of the lake remain unfrozen due to geothermal inflow, reinforcing the idea that Mývatn operates as a hybrid system—neither purely lacustrine nor purely geothermal.

From a geological standpoint, Mývatn is best understood as a volcanically mediated lake, where lava architecture defines basin geometry, permeability, and hydrological pathways. The lake’s form is therefore inseparable from the surrounding volcanic terrain; it is not simply set within the landscape, but constructed by it.

Hydrology, chemistry, and geothermal influence

Hydrologically, Mývatn is shallow—averaging less than 3 metres in depth—which has profound consequences for temperature regulation, nutrient cycling, and biological productivity. The lake is fed primarily by groundwater inflow rather than surface rivers, a feature that stabilizes chemical composition while allowing geothermal influence to remain pronounced.

Geothermal springs introduce dissolved minerals and heat, enhancing primary productivity and preventing prolonged ice cover in certain areas. This results in extended growing seasons for algae and aquatic plants, which in turn support dense populations of invertebrates. The name “Mývatn,” meaning “Midge Lake,” reflects this ecological outcome rather than a superficial annoyance: midges are a keystone species here, transferring nutrients from aquatic to terrestrial systems.

Chemically, the lake exhibits relatively high alkalinity and nutrient availability compared to other Icelandic lakes. These conditions are not anthropogenic but geologically driven, arising from basalt weathering and geothermal inputs. This distinguishes Mývatn from eutrophic lakes elsewhere, where nutrient loading is often associated with human activity.

Mývatn has long served as a natural laboratory for studying ecosystem responses to volcanic forcing. Long-term ecological research conducted in the area has contributed to global understanding of trophic dynamics, resilience, and feedback mechanisms in nutrient-rich freshwater systems.

Ecology and biological significance

Despite its northern latitude, Lake Mývatn supports one of the most productive freshwater ecosystems in Iceland. Its shallow depth allows sunlight to penetrate much of the water column, stimulating photosynthesis and supporting extensive algal growth. This primary productivity underpins the lake’s extraordinary biodiversity.

Mývatn is internationally recognized for its birdlife, particularly waterfowl. It hosts one of the highest densities of breeding duck species in Europe, including globally significant populations of Barrow’s goldeneye and harlequin duck. The abundance of aquatic insects—especially midges—provides a reliable food source that sustains these populations through the breeding season.

Importantly, this biodiversity is spatially structured. Different parts of the lake support distinct ecological communities depending on depth, geothermal influence, and substrate type. Lava shelves, soft sediment basins, and spring-fed zones each host different assemblages, reinforcing the lake’s heterogeneity.

The ecological value of Mývatn has been formally recognized through conservation designations, including protected area status. However, protection here is not about exclusion but about managing coexistence between tourism, agriculture, and ecological integrity. The lake remains a working landscape, shaped by grazing, settlement, and seasonal visitation.

Human presence and cultural landscape

Human settlement around Lake Mývatn dates back to Iceland’s early settlement period. The lake’s productivity—fish, birds, fertile soils—made it an attractive location despite its volcanic volatility. Farms established here adapted to periodic eruptions, ash fall, and shifting ground conditions, reinforcing a culture of environmental responsiveness rather than control.

Historically, the lake supported fishing, bird egg collection, and hay production, integrating aquatic and terrestrial resources into a single subsistence system. These practices have declined or transformed, but their imprint remains visible in land use patterns and place names.

In the modern era, Mývatn has become a focal point for tourism in North Iceland. Unlike single-feature destinations, the lake offers a distributed experience: lava formations, geothermal areas, wetlands, and viewpoints dispersed around the basin. This dispersal reduces pressure on any single site but requires careful visitor management to protect sensitive habitats.

Culturally, Mývatn occupies a distinct position in Icelandic identity. It is neither remote highland nor urban centre, but a lived-in volcanic landscape where daily life continues in close proximity to active geological processes. This continuity is central to its authenticity.

Experiencing Mývatn—scale, restraint, and interpretation

Experiencing Lake Mývatn effectively requires a shift in expectations. This is not a destination defined by dramatic vertical relief or singular landmarks, but by cumulative detail. Its power lies in repetition and variation: lava shapes recurring with subtle differences, water levels changing with season, steam appearing and disappearing with wind.

Access around the lake is straightforward, with roads and pull-offs providing entry points to key features. However, many of the most sensitive areas—wetlands, pseudocraters, bird nesting zones—require restraint and adherence to marked paths. The ecological productivity that defines Mývatn is also what makes it vulnerable to disturbance.

Seasonality reshapes the experience profoundly. Summer brings life density—birds, insects, vegetation—while winter emphasizes geothermal contrast, silence, and structural clarity. Neither season is secondary; each reveals different aspects of the system.

As a destination, Mývatn rewards informed attention. Understanding why the lake looks as it does—why it is shallow, why it is green, why steam rises at its margins—transforms observation into comprehension. This is a place where explanation enhances, rather than diminishes, experience.

Interesting facts:

- Lake Mývatn is approximately 2,300 years old, making it geologically young.

- The lake’s name refers to midges, a keystone species in its ecosystem.

- Mývatn hosts one of Europe’s highest concentrations of breeding duck species.

- Much of the lake is fed by geothermal groundwater, not surface rivers.

- The pseudocraters at Skútustaðir are steam explosion features, not true volcanic cones.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Work at human scale: foreground lava and shoreline features anchor wide scenes.

- Soft light excels: overcast conditions enhance color and reduce surface glare.

- Season matters: summer emphasizes ecology; winter emphasizes structure and steam.

- Avoid trampling: fragile soils and wetlands scar easily and recover slowly.

- Tell sequences: Mývatn is best captured as a series, not a single frame.