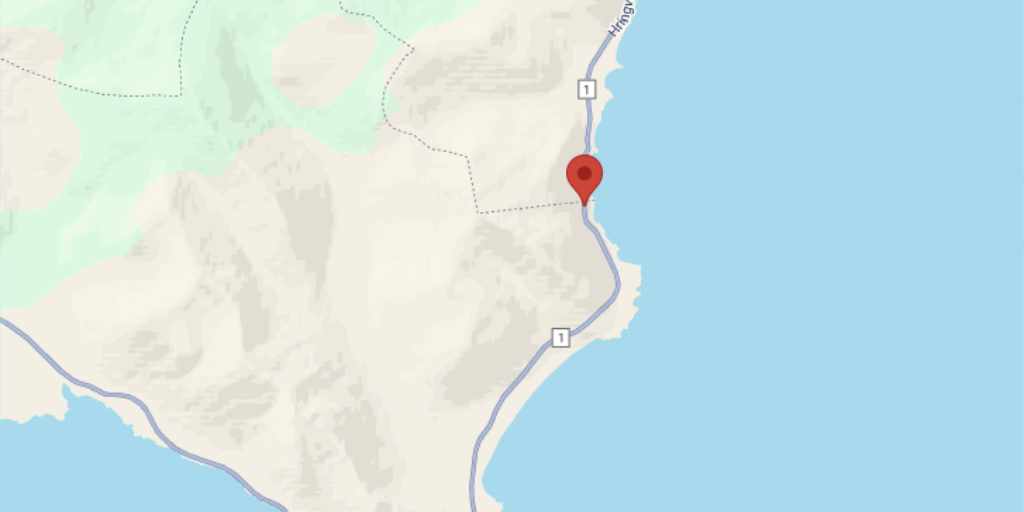

Hvalnesskriður is one of the most breathtaking and, at times, intimidating sections of Iceland’s Ring Road. Wedged between steep basalt cliffs and the endless expanse of the North Atlantic, the road clings to a narrow shelf carved by both nature and human engineering. Travelers who pass through experience both awe and respect for this place where geology, weather, and human persistence collide.

Hvalnesskriður coastal road

Hvalnesskriður lies on the eastern coast of Iceland between the headland of Hvalnes and the sheltered waters of Lónsfjörður. The Icelandic word “skriður” refers to landslides or scree slopes, and the name accurately describes the unstable talus fields that cascade down the cliffs above the road. This area belongs geologically to the Tertiary basalt formations that dominate much of East Iceland. These rocks were formed by repeated volcanic eruptions 6–12 million years ago, building up layer upon layer of basalt that was later sculpted by the Ice Age glaciers.

The coastal profile here is particularly striking because the basaltic strata tilt seaward, creating unstable slopes that are prone to collapse. Over time, rockfalls and landslides have reshaped the cliff face, sometimes cutting off access to the road altogether. The cliffs form the eastern flank of the Vestrahorn–Eystrahorn mountains, whose sharp ridges rise steeply above the narrow shelf of the Ring Road. The Atlantic Ocean is only meters away, often crashing against the roadside in stormy conditions. This juxtaposition of oceanic force and mountain geology makes Hvalnesskriður an iconic example of Iceland’s raw coastal landscape.

Historically, this section of the coast was among the most feared passages in East Iceland. Before the completion of the Ring Road in 1974, access between the fishing villages of Djúpivogur and Höfn was extremely difficult, often requiring long detours over mountain passes or by sea. Once the road was carved into the scree slopes of Hvalnesskriður, it quickly earned a reputation for danger. Rockslides were frequent, winter storms could block travel for days, and drivers were forced to navigate the narrow track with the ocean breaking at their wheels.

Over the years, road authorities have carried out extensive safety work. Protective barriers, drainage channels, and reinforcement of unstable slopes have been added. Nevertheless, Hvalnesskriður remains a place where nature dictates the terms of passage. Even today, travelers are advised to check conditions on road.is

before attempting the drive, as closures due to falling rocks or storm damage are not uncommon.

This area also has cultural resonance. Situated between the radar stations of Stokksnes and Eystrahorn, Hvalnesskriður was within a Cold War surveillance zone where Iceland’s coastline played a role in NATO monitoring of Soviet activity in the North Atlantic. The road, therefore, is not only a link in Iceland’s transportation system but also a historical corridor where global geopolitics once brushed against local realities.

For modern visitors, Hvalnesskriður offers one of the most scenic coastal drives in Iceland. To the west, the jagged profile of Vestrahorn dominates the horizon, while to the east the sharp ridge of Eystrahorn rises abruptly from the sea. Between them, the road curves in a series of dramatic sweeps, clinging to the cliff while the Atlantic surges below.

The natural environment is equally remarkable. The cliffs host colonies of seabirds, while seals can sometimes be seen hauled out on the rocky shorelines. Offshore, drift ice occasionally drifts south from the Arctic, reminding travelers of the subpolar forces that shape this coastline. Just inland lies the wetland basin of Lónsfjörður, a habitat for migratory birds and a peaceful contrast to the raw energy of the coast.

Driving here is both thrilling and humbling. The grandeur of the mountains, the immediacy of the sea, and the knowledge of the road’s precarious history combine to create a powerful sense of place. Hvalnesskriður is more than a transit point on Route 1—it is a destination in itself, encapsulating the drama and fragility of Iceland’s eastern seaboard.

Interesting facts:

-

- The Icelandic Road Administration has had to clear significant rockslides here multiple times in recent decades, sometimes closing the Ring Road for days.

- The name “Hvalnes” means “Whale Point,” a reference to the marine life historically seen offshore.

- The nearby Hvalnes lighthouse, built in 1954, remains an important navigational aid for ships.

- Lónsfjörður lagoon, just beyond Hvalnesskriður, is one of Iceland’s oldest protected nature reserves (since 1977).

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

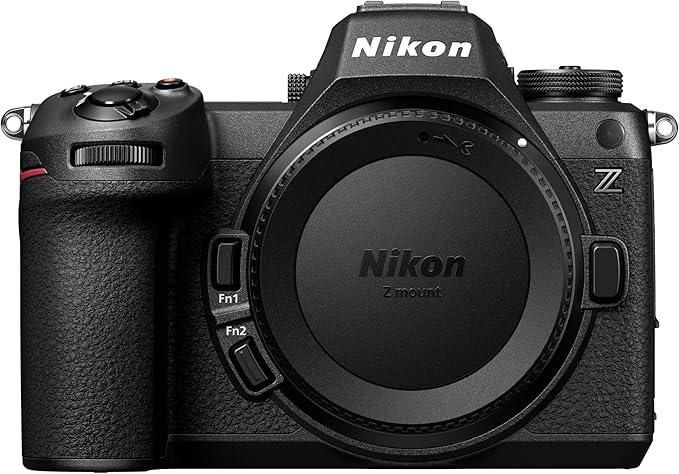

Photography tips:

- Golden Hour: Morning light when driving west to east illuminates the scree slopes and cliffs with warm tones.

- Leading Lines: Use the curving Ring Road as a visual element leading into the towering backdrop of Vestrahorn or Eystrahorn.

- Stormy Drama: Capture waves smashing against the road during unsettled weather—just take care with equipment in salt spray.

- Long Exposure: Smooth out the Atlantic surf against the black rocks for atmospheric landscape shots.

- Minimalism: Fog