Located in Northeast Iceland within Vatnajökull National Park, Hljóðaklettar lies along the Jökulsá á Fjöllum river corridor, downstream from Dettifoss and upstream from Ásbyrgi. Often referred to as the “Echo Cliffs,” Hljóðaklettar presents a rare concentration of lava arches, column clusters, and eroded cavities—formed through volcanic deposition and later sculpted by water and wind.

The location of Hljóðaklettar Echo Rocks

Latitude

65.9489

Longitude

-16.5146

Hljóðaklettar Echo Rocks

Volcanic origin and lava architecture

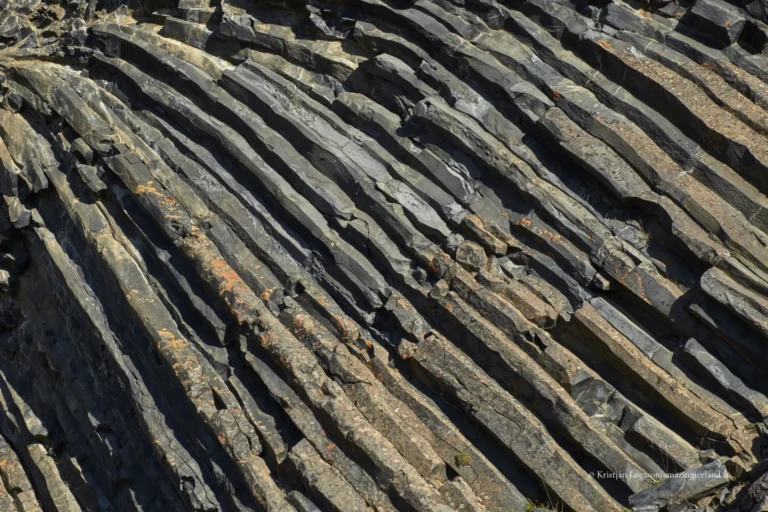

Hljóðaklettar is composed primarily of basalt lava flows emplaced during eruptions in Iceland’s Northern Volcanic Zone. Unlike simple sheet flows or columnar cliff faces, the lava here cooled unevenly, producing zones of variable thickness, internal voids, and structural weakness.

Some formations at Hljóðaklettar are related to lava ponding and partial collapse, while others reflect erosional modification of pre-existing lava architecture. The result is a landscape dominated by arches, alcoves, freestanding pillars, and hollowed walls, rather than continuous surfaces.

The basalt columns here are often irregular and curved, deviating from the classic vertical hexagonal patterns seen at sites like Aldeyjarfoss. This irregularity is key: it creates cavities and overhangs that later acted as focal points for erosion and acoustic resonance.

From a geological perspective, Hljóðaklettar represents a hybrid landform—constructed volcanically, then selectively removed by fluvial and atmospheric processes. What remains is not the lava itself, but its structural skeleton.

Erosion, acoustics, and sensory scale

The name Hljóðaklettar translates to “Echo Rocks,” a reference to the site’s unusual acoustic properties. Sound waves reflect off concave basalt surfaces, amplify within cavities, and travel unpredictably between formations. These effects are not incidental; they are direct consequences of geometry, surface hardness, and spatial enclosure.

Erosional processes played a crucial role in producing this geometry. During periods of higher discharge—likely linked to past flooding in the Jökulsá á Fjöllum system—water exploited weak zones within the basalt, enlarging cavities and sharpening edges. Wind erosion and freeze–thaw cycles further refined these forms.

Unlike Dettifoss or Ásbyrgi, Hljóðaklettar does not overwhelm through scale. Its impact is experiential rather than monumental. The formations are best understood at close range, where human presence activates the landscape through sound and movement.

Academically, the site demonstrates how secondary processes—erosion and weathering—can transform otherwise ordinary lava into spatially complex and perceptually active terrain.

Relationship to the Jökulsá á Fjöllum system

Hljóðaklettar forms part of a broader geomorphological sequence along the Jökulsá á Fjöllum. Upstream, the river concentrates energy vertically at Dettifoss; downstream, it expands laterally at Ásbyrgi. At Hljóðaklettar, energy is neither fully concentrated nor fully dissipated—it is redirected into form.

This intermediate position explains the site’s hybrid character. It is neither canyon nor waterfall, but a sculptural field shaped by fluctuating flow regimes. The absence of a major present-day channel reinforces the idea that Hljóðaklettar records past hydrological conditions, not current ones.

In this sense, Hljóðaklettar functions as a geological memory—preserving traces of river behavior that no longer occurs at visible scale.

Cultural perception and naming

Like many Icelandic landscapes defined by unusual form, Hljóðaklettar acquired its name through sensory association rather than visual dominance. Sound, rather than sight, became the defining feature, embedding the place in oral experience and local knowledge.

Such naming practices reflect Icelandic landscape literacy: places are often identified by how they behave rather than how they look. In this context, Hljóðaklettar’s echoes are not curiosities but diagnostic traits—signals of enclosure, hardness, and spatial complexity.

While the site is not heavily embedded in formal mythology, its atmosphere aligns closely with Icelandic concepts of liminality—spaces that feel transitional, unstable, or perceptually altered.

Visiting Hljóðaklettar—movement, access, and care

Hljóðaklettar is accessed via a short walk from the Ásbyrgi area, with marked trails guiding visitors through and around the formations. The terrain is uneven but manageable, emphasizing exploration at walking pace rather than distant viewing.

Climbing on formations is discouraged. Many arches and pillars are structurally delicate, and human weight accelerates degradation. Trails are designed to balance proximity with preservation, and staying on them is essential for long-term stability.

The site rewards quiet. Reducing ambient noise allows the acoustic character to emerge naturally, turning the visit into an interactive experience rather than a visual checklist.

Seasonality affects accessibility and mood. In winter, snow softens edges and dampens sound, shifting emphasis toward form. In summer, dry basalt enhances acoustic clarity and contrast.

Hljóðaklettar in interpretive context

Within the Jökulsá á Fjöllum corridor, Hljóðaklettar provides a critical interpretive link. It demonstrates that erosion does not always simplify landscapes; under certain conditions, it increases complexity, carving absence into presence.

Seen alongside Dettifoss, Selfoss, and Ásbyrgi, Hljóðaklettar reinforces a core theme of Northeast Iceland: extreme systems leave behind subtle traces as well as monumental ones. Understanding both is essential to reading the landscape accurately.

Interesting facts:

- Hljóðaklettar translates to “Echo Rocks.”

- The formations are made of irregularly cooled basalt, not classic uniform columns.

- Acoustic effects result from concave rock geometry, not artificial amplification.

- The site records past river activity rather than current flow conditions.

- Hljóðaklettar lies within the same protected river corridor as Dettifoss and Ásbyrgi.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Work close: details and negative space matter more than wide vistas.

- Use people for scale: formations appear abstract without reference.

- Side light enhances texture: low sun reveals cavities and curvature.

- Avoid clutter: simple compositions suit complex forms.

- Respect fragility: do not climb for angles—perspective exists at ground level.