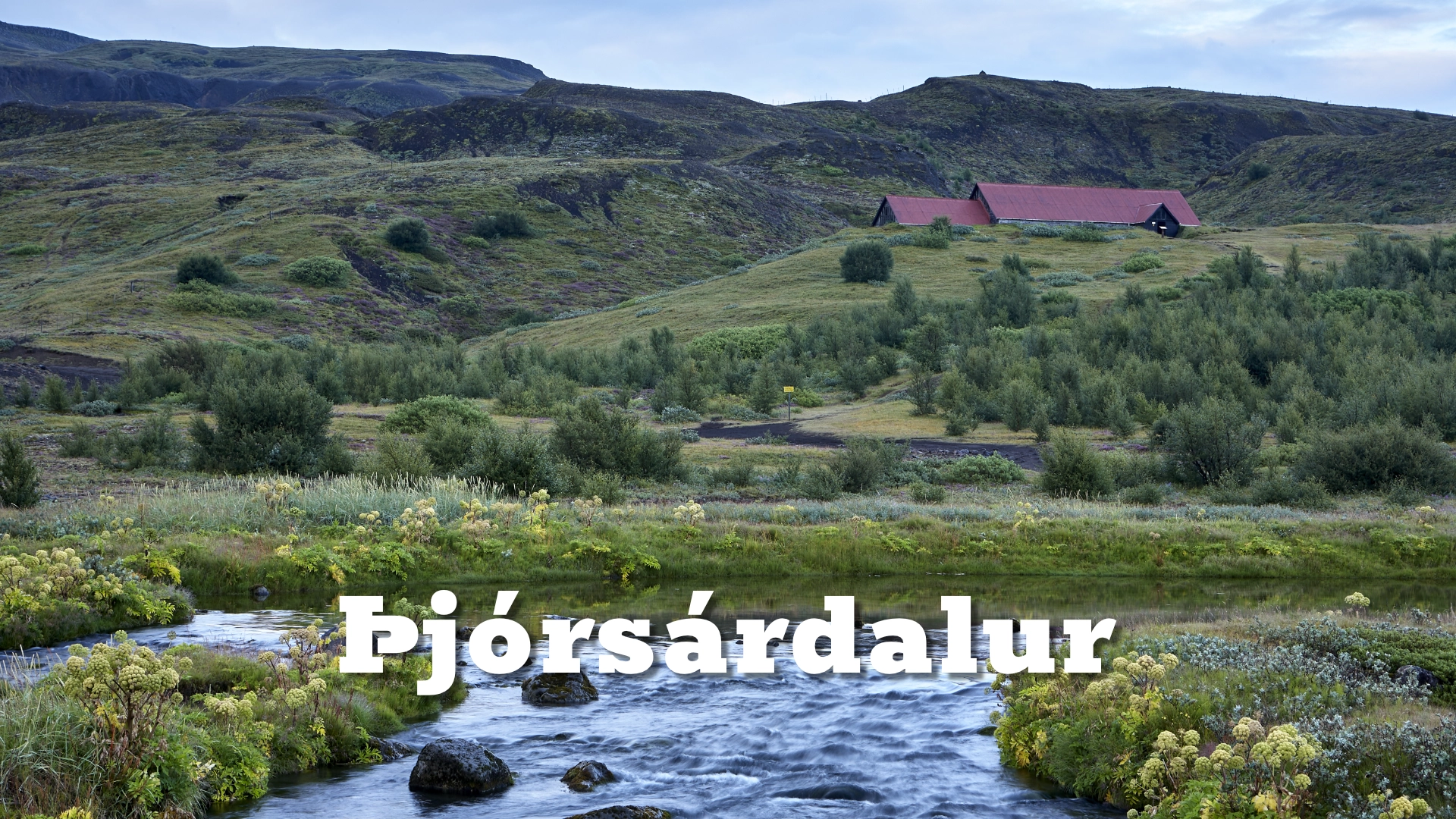

East of the river Þjórsá, in South Iceland, Þjórsárdalur stretches from cultivated lowlands toward the interior highlands. The valley lies within an active volcanic zone, influenced historically by eruptions from Hekla, and shaped continuously by glacial meltwater and sediment transport.

The location of Þjórsárdalur valley

Latitude

64.0469

Longitude

-19.9495

Þjórsárdalur valley

Þjórsárdalur occupies a transitional landscape between Iceland’s interior plateau and its southern agricultural belt. The valley floor consists largely of lava fields, glacial sediments, and tephra deposits derived from repeated volcanic events. Over time, erosion by tributaries of the Þjórsá river system has carved smaller canyons and formed fertile pockets within otherwise coarse substrate.

The valley’s modern appearance is deceptively stable. Beneath grass and moss layers lie extensive ash deposits from major eruptions, most notably Hekla’s eruption in 1104, which had severe consequences for medieval farms in the region. Tephrochronological studies confirm thick ash layers corresponding to this eruption across the valley.

From a geomorphological perspective, Þjórsárdalur is defined by alternating periods of settlement and disturbance, rather than uninterrupted development.

Archaeological evidence demonstrates that Þjórsárdalur supported multiple farms during the settlement period. Excavations at sites such as Stöng reveal longhouse structures buried beneath volcanic ash, preserving valuable insight into early Icelandic architecture and daily life.

The reconstructed farmhouse at Stöng provides a controlled interpretation of this medieval environment, based on excavated remains rather than speculative design. The site illustrates how settlement expanded into marginal valleys during favorable climatic periods before being disrupted by volcanic events.

The 1104 eruption of Hekla appears to have marked a turning point for sustained habitation in parts of the valley, though abandonment was not necessarily immediate or uniform. Settlement patterns fluctuated with environmental stability.

Hydrologically, Þjórsárdalur is closely tied to the Þjórsá river system, Iceland’s longest river. Tributaries descending from the highlands have carved side gorges, including formations such as Gjáin, where basalt walls, waterfalls, and vegetated microclimates contrast sharply with surrounding lava plains.

Waterfalls such as Hjálparfoss mark geological boundaries between lava flows and sediment layers. These features demonstrate how fluvial erosion exploits structural weaknesses in volcanic bedrock.

The valley therefore expresses both volcanic deposition and river incision simultaneously, making process overlap clearly visible.

Modern Þjórsárdalur includes significant hydroelectric infrastructure. Reservoirs and power stations along the Þjórsá river harness glacial meltwater descending from the highlands. These developments have altered hydrological regimes while maintaining overall valley form.

The presence of energy infrastructure situates Þjórsárdalur within Iceland’s broader relationship with renewable resources. The same glacial and volcanic forces that disrupted medieval settlement now underpin national electricity production.

This juxtaposition of archaeological heritage and contemporary engineering defines the valley’s modern identity.

Ecologically, Þjórsárdalur supports birch woodland regeneration projects, reflecting national efforts to restore native vegetation historically reduced by grazing and erosion. The valley’s relatively sheltered microclimate allows more substantial vegetation growth than adjacent highland areas.

Seasonal variation is pronounced. Snow cover persists through winter, while summer reveals layered textures of grass, lava, and ash. Visibility of Hekla to the south reinforces the valley’s connection to active volcanism.

Interesting facts:

- Þjórsárdalur was heavily affected by Hekla’s 1104 eruption.

- Excavations at Stöng reveal a medieval longhouse preserved in ash.

- The valley contains waterfalls such as Hjálparfoss and canyons like Gjáin.

- It lies along Iceland’s longest river, Þjórsá.

- The region includes major hydroelectric installations.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Work with layers: Include lava, vegetation, and distant Hekla when possible.

- Overcast light suits ash fields: It reduces contrast and reveals texture.

- Use elevation near Gjáin: Depth and structure read best from above.

- Avoid isolating features: The valley’s meaning lies in combined systems.

- Seasonal awareness: Summer greenery contrasts strongly with dark lava.