On the southern edge of the Westfjords, Rauðisandur extends for several kilometers along an open bay, facing the North Atlantic. Unlike Iceland’s dark volcanic beaches, Rauðisandur’s fine, mineral-rich sands and broad intertidal zone create a coastal environment defined by color variation, low relief, and a strong sense of spatial openness.

The location of Rauðisandur red sand beach

Latitude

65.4886

Longitude

-23.9859

Rauðisandur red sand beach

Rauðisandur is located south of the Látrabjarg cliffs, forming a long, gently curving shoreline backed by low dunes and steep mountain slopes. The beach stretches for approximately 10 kilometers, making it one of the longest continuous sandy beaches in Iceland. Its width and shallow gradient produce an expansive intertidal zone that changes character dramatically with the tide.

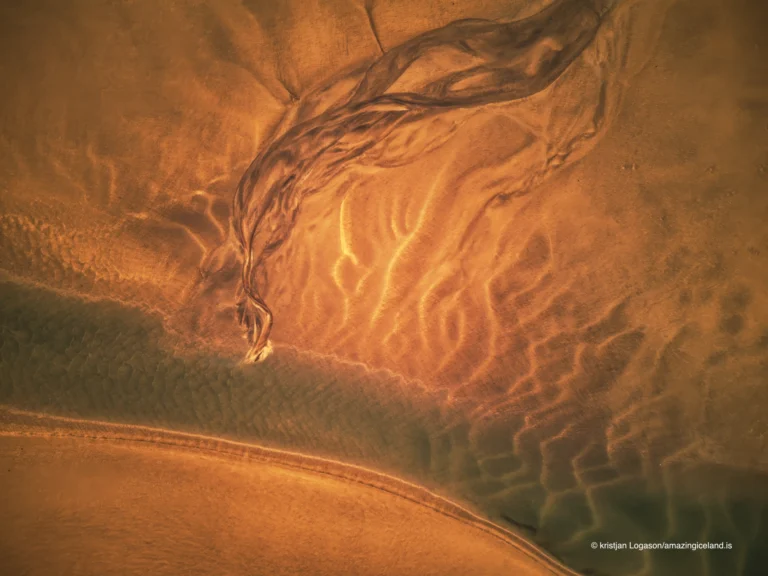

The sand itself distinguishes the site immediately. Unlike the basalt-derived black sands that dominate much of Iceland’s coastline, Rauðisandur’s sediment contains a high proportion of shell fragments and lighter minerals, which scatter light differently and produce warm tones. Depending on weather and angle of light, the beach can appear rust-red, golden, or almost pale beige. The name Rauðisandur—“Red Sand”—reflects this variability rather than a single, fixed color.

The openness of Rauðisandur is central to its character. There are no cliffs enclosing the beach itself, no stacks interrupting the shoreline, and no built infrastructure along its length. The surrounding mountains frame the bay at a distance, but the beach remains visually uninterrupted, creating a strong sense of exposure and scale.

This exposure also governs conditions. Weather systems move across the bay with little obstruction, and wind can reshape surface patterns within hours. Tidal variation is pronounced, and the distance between high and low tide can be substantial. At low tide, the beach expands into a wide, reflective plain; at high tide, the sea advances quietly, compressing the shoreline back toward the dunes.

Ecologically, Rauðisandur supports birdlife adapted to open coastal habitats. The intertidal zone provides feeding grounds, while the absence of heavy human activity allows seasonal patterns to remain relatively undisturbed. The landscape’s apparent simplicity conceals a finely balanced system dependent on sediment supply, wave regime, and weather variability.

Human presence at Rauðisandur has always been limited. The beach lies far from major settlements, and access involves steep gravel roads that descend from the interior of the Westfjords. This approach reinforces the sense of transition: from enclosed fjords and mountain passes to sudden openness at sea level.

Historically, the area supported small-scale farming and coastal use, but never at a density that significantly altered the beach itself. Unlike harbored fjords, Rauðisandur offered little protection for permanent maritime infrastructure. Its value lay in access to resources rather than control over them.

This limited intervention is key to the beach’s current state. Rauðisandur remains a working natural system rather than a managed recreational space. There are no formal promenades, no constructed viewpoints, and minimal signage. Observation here depends on self-regulation and environmental awareness.

Rauðisandur is often described as visually surprising, but its real distinction lies in contrast within the Icelandic context. Where much of the country’s coastline emphasizes verticality—cliffs, stacks, and narrow coves—Rauðisandur emphasizes breadth. The eye moves laterally rather than upward, following the shoreline instead of resisting it.

This lateral emphasis alters perception of distance and time. Walking along Rauðisandur feels slower, not because of difficulty, but because scale is stretched. Landmarks are distant, and progress is measured subtly. The beach invites movement without urgency.

Rauðisandur is an instructive counterexample within Iceland’s coastal typology. It demonstrates how sediment composition, wave exposure, and coastal geometry can override volcanic dominance, producing a shoreline that feels almost anomalous within the national landscape.

Ultimately, Rauðisandur is defined by restraint. It does not compress experience into a single viewpoint or feature. Instead, it unfolds gradually, rewarding time and attentiveness. Color shifts, tide movement, and weather interaction provide the narrative rather than landmarks.

Rauðisandur complements fjords, cliffs, and lava fields by introducing horizontal scale and tonal subtlety. It shows that Iceland’s landscapes are not uniformly dramatic, but selectively expressive—capable of quiet as well as force.

Rauðisandur is not empty. It is open.

Interesting facts:

- Rauðisandur stretches for approximately 10 km, making it one of Iceland’s longest beaches.

- The sand’s color comes from shell fragments and light minerals, not volcanic basalt.

- The beach lies south of Látrabjarg, Europe’s westernmost seabird cliffs.

- Tidal variation creates a very wide intertidal zone.

- The area remains largely undeveloped, preserving natural coastal processes.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Work with tide tables: Low tide emphasizes scale; high tide simplifies composition.

- Let color breathe: Avoid over-saturation—tones shift naturally with light and moisture.

- Use long horizons: Wide frames suit the beach’s lateral emphasis.

- Include distance markers: Distant cliffs or headlands help communicate scale.

- Weather is an asset: Overcast conditions often produce the most accurate color and texture.