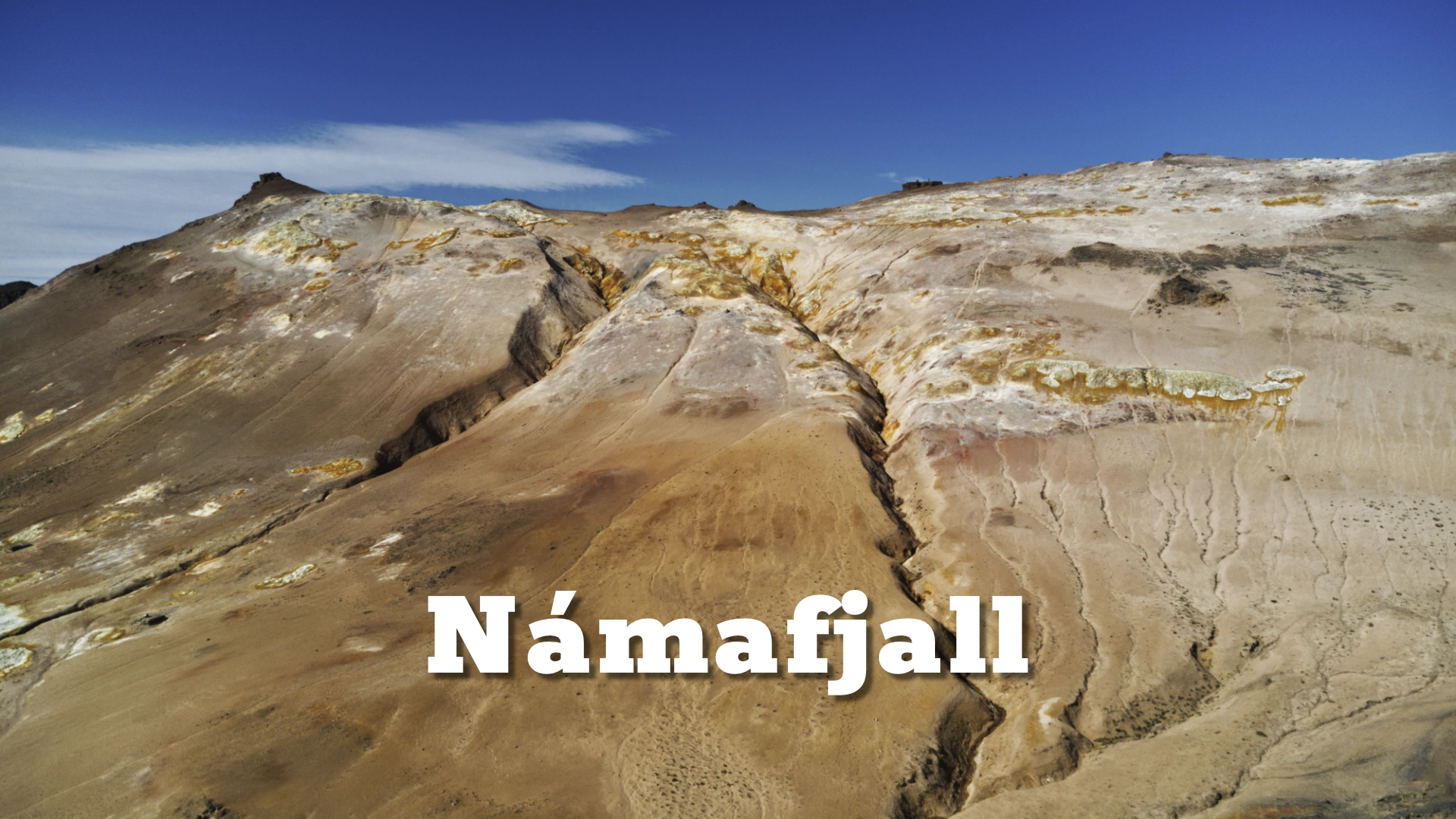

East of Lake Mývatn, at the foot of Námafjall mountain, the geothermal field of Námaskarð offers a concentrated encounter with Iceland’s high-temperature geothermal systems. Unlike landscapes shaped primarily by lava flows, this area is defined by heat, gas, and water interacting at shallow depth—making it one of the most direct and educational geothermal sites in the country.

The location of Námafjall sulphur mountain in north Iceland

Latitude

65.6419

Longitude

-16.8088

Námafjall sulphur mountain in north Iceland

Geological setting and geothermal origins

Námafjall lies within the active rift environment of North Iceland and forms part of the wider Krafla volcanic system. This location is critical: Námafjall sits above zones where magma intrusions, faulting, and high heat flow combine to drive vigorous hydrothermal circulation.

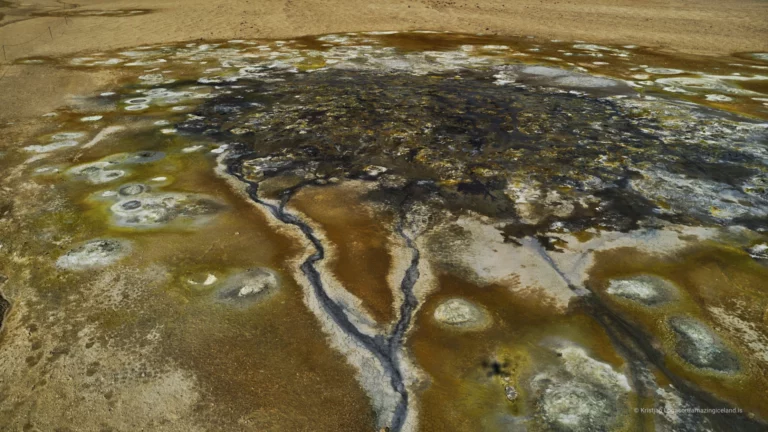

The geothermal manifestations at Námaskarð are primarily high-temperature fumarolic features, including steam vents, sulfur fumaroles, and boiling mud pools. These occur where groundwater descends through fractured basalt, becomes superheated at depth, and returns to the surface as steam and gas. Unlike geysers, which require specific plumbing geometry, fumaroles represent open, unstable pathways—constantly reshaped by mineral deposition and pressure changes.

The vivid coloration of the ground—yellows, reds, whites, and greys—is not decorative but diagnostic. Yellow sulfur precipitates directly from volcanic gases, while iron oxides and altered clays record oxidation and hydrothermal alteration of basalt. Over time, these processes weaken the rock, creating soft, unstable surfaces that are visually striking but mechanically fragile.

Historically, Námafjall has also been a site of sulfur extraction, particularly in the 19th century, when sulfur was mined for export and industrial use. This human interaction underscores the same principle that defines modern geothermal exploitation: surface chemistry is a usable resource, but only where geology allows repeated access to heat and reactive compounds.

Námafjall as a chemical landscape

What distinguishes Námafjall from many other geothermal sites in Iceland is its chemical dominance over morphology. There are no large lava fields here to read eruptive history; instead, the landscape is constantly re-authored by gas flux, condensation, and mineral precipitation. In academic terms, this is an environment where geothermal alteration exceeds volcanic construction at the surface.

Hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) is the most immediately noticeable gas, responsible for the area’s characteristic smell. When oxidized near the surface, it forms elemental sulfur and sulfuric acid—both of which actively transform surrounding rock. Clay minerals form rapidly, reducing permeability and occasionally sealing vents, which may then reopen elsewhere. This explains why the field appears dynamic even without eruptive activity: the system reorganizes itself continuously.

Temperature measurements in the Námafjall field commonly exceed 100°C at shallow depth, with steam vents reaching significantly higher temperatures. These conditions classify the area as a high-enthalpy geothermal system, similar in thermal regime to those exploited for power generation elsewhere in the Krafla region. However, at Námafjall, the energy is left largely uncontained, making it an open-air laboratory for geothermal processes.

Scientifically, this visibility is invaluable. Processes that occur unseen in many geothermal reservoirs—scaling, alteration, gas separation—are exposed here at human scale. For visitors, this means Námafjall offers not only sensory impact but conceptual clarity: you can see, smell, and hear the interactions that power Iceland’s geothermal narrative.

Visiting Námafjall—experience, access, and limits

Námafjall is one of the most accessible geothermal areas in North Iceland, located directly along Route 1 (the Ring Road). Boardwalks and marked paths guide visitors through the most active zones, balancing proximity with safety. These routes are not arbitrary; they are designed to avoid areas where the ground crust may be thin, unstable, or dangerously hot beneath the surface.

Stepping off marked paths is particularly hazardous here. Unlike lava fields, which are structurally solid once cooled, geothermal ground can conceal boiling mud or steam beneath a deceptively firm crust. Burns and collapses are real risks, not hypothetical warnings. From a conservation standpoint, footprints also disrupt fragile clay surfaces that may take decades to visually recover.

The experience itself is intense but compact. Námafjall is not a place for long hikes or quiet contemplation; it is a site of exposure and immediacy. Steam obscures and reveals features with changing wind, soundscape is dominated by hissing vents, and the smell of sulfur is unavoidable. This sensory density is precisely what makes the site effective—it communicates geothermal power without explanation panels.

In the broader context of the Mývatn region, Námafjall functions as a counterpoint to calmer volcanic features. Where craters and lava fields speak of past events, Námafjall insists on the present tense. The system is active, reactive, and ongoing—reminding visitors that Iceland’s volcanic energy is not only historical but continuous.

Interesting facts:

- Námafjall’s geothermal field is commonly known as Hverir, meaning “hot springs,” though true springs are secondary to fumaroles here.

- The area was historically mined for elemental sulfur, visible today as bright yellow deposits near vents.

- Námafjall sits within a high-temperature geothermal zone, with shallow subsurface temperatures exceeding boiling point.

- Gas and mineral output can shift vent locations over time as pathways seal and reopen.

- The site lies only a short distance from active geothermal power production, illustrating different expressions of the same heat source.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Compose with texture, not distance: Námafjall rewards close-to-mid-range compositions emphasizing mud, mineral crusts, and steam.

- Watch wind direction: steam density changes rapidly and can either simplify or obscure a scene within seconds.

- Use muted color profiles: the ground is naturally saturated; restrained processing preserves scientific credibility.

- Include scale carefully: boardwalk edges or distant figures can help contextualize size without visual clutter.

- Protect equipment: acidic moisture and fine mineral dust can accumulate quickly near active vents.