Located in Iceland’s central highlands, Langjökull is the country’s second-largest glacier and one of its most structurally important. Feeding major river systems, influencing regional climate, and preserving deep records of past conditions, Langjökull is less a destination than a foundational element in Iceland’s physical geography.

The location of Langjökull glacier

Latitude

64.6597

Longitude

-20.3776

Langjökull glacier

Langjökull covers an area of approximately 925 square kilometres, making it Iceland’s second-largest glacier after Vatnajökull. It occupies a highland plateau west of the central volcanic zone, spanning parts of the interior between Borgarfjörður, Árnessýsla, and the Kjölur route. Unlike outlet-dominated glaciers with dramatic tongues, Langjökull presents as a broad, gently sloping ice cap, its scale revealed through extent rather than relief.

The glacier rests atop a volcanic substrate shaped by repeated eruptive phases and subglacial activity. Basal melting, pressure, and geothermal influence interact beneath the ice, contributing to complex internal drainage systems. While Langjökull is not associated with frequent explosive subglacial eruptions, its bedrock context places it within Iceland’s active geological framework.

From a geomorphological perspective, Langjökull functions as a source glacier. Its importance lies in what flows outward: meltwater, sediment, and long-term erosional force distributed through connected river systems.

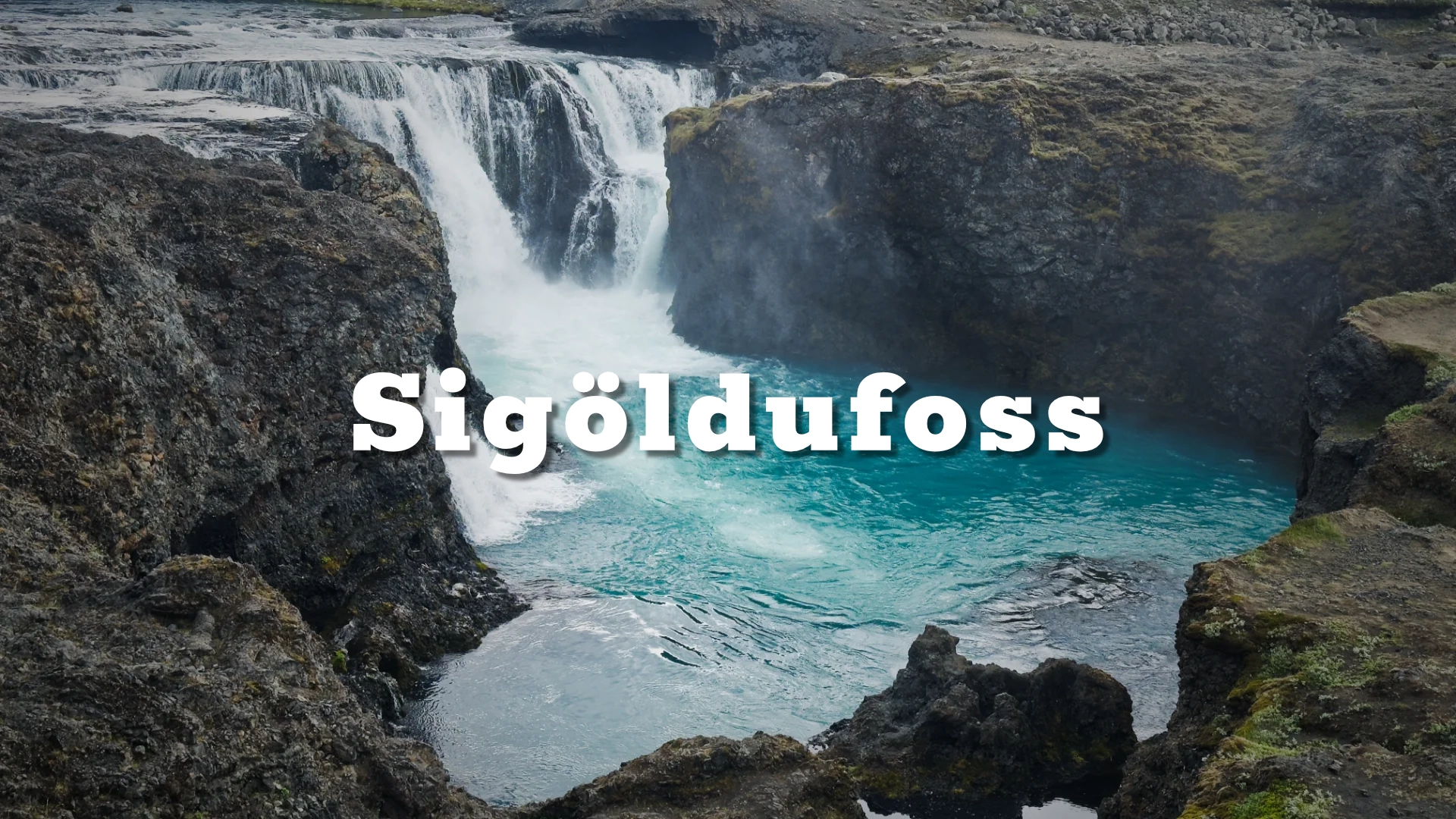

Several of Iceland’s most significant rivers originate from Langjökull, including the Hvítá, Þjórsá, and Norðurá. These rivers shape landscapes far from the glacier itself, carving canyons, feeding waterfalls, and supporting ecosystems and settlement across southwest and west Iceland.

The connection between Langjökull and downstream features such as Gullfoss underscores the glacier’s indirect visibility. Even where ice is no longer present, its influence remains legible in river volume, sediment load, and seasonal variation.

Hydrologically, Langjökull acts as a buffer system. Meltwater release moderates seasonal flow, storing precipitation as ice before gradual redistribution. As the glacier retreats under contemporary warming, this buffering capacity diminishes, altering river behavior and downstream stability.

Climatologically, Langjökull serves as a valuable archive of atmospheric history. Ice cores extracted from the glacier preserve layered records of snowfall, volcanic ash, and atmospheric composition, offering insight into Iceland’s past climate variability. These records complement marine and terrestrial proxies, contributing to broader North Atlantic climate research.

Like all Icelandic glaciers, Langjökull has experienced sustained retreat over recent decades. Thinning margins, reduced accumulation zones, and increased melt rates reflect regional temperature rise. While visually subtle compared to smaller outlet glaciers, these changes are measurable and significant.

The glacier’s gradual retreat also exposes new terrain—freshly scoured bedrock and sediment plains—creating transient landscapes that are quickly colonized by pioneer species. This process highlights the glacier’s role not only as an erosional force, but as a regulator of ecological succession.

Human interaction with Langjökull has historically been limited by access and scale. The glacier occupies a remote highland environment, subject to rapid weather change, limited infrastructure, and seasonal constraints. Traditionally, Langjökull functioned more as a barrier than a destination, influencing travel routes rather than inviting visitation.

In recent decades, controlled access has increased through guided expeditions, research activity, and engineered features such as artificial ice tunnels. These developments provide insight into glacial structure without altering the glacier’s fundamental character. Importantly, access remains regulated and conditional, reinforcing the understanding that Langjökull is not a recreational landscape in the conventional sense.

Culturally, the glacier has remained understated. Unlike glaciers tied to saga narratives or dramatic calving fronts, Langjökull occupies a quieter role—as infrastructure of nature rather than symbol. Its presence is felt through consequence rather than representation.

Langjökull ultimately defines itself through connection. It links highland precipitation to lowland rivers, volcanic history to present climate, and deep time to current change. Its surface may appear uniform, but its effects are distributed widely and unevenly across Iceland.

Interesting facts:

- Langjökull is Iceland’s second-largest glacier, covering ~925 km².

- It feeds major rivers including Hvítá, Þjórsá, and Norðurá.

- The glacier acts as a hydrological buffer, storing and releasing water seasonally.

- Ice cores from Langjökull contribute to climate research.

- Sustained retreat has been documented over recent decades.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Think in scale, not drama: Aerial or elevated viewpoints best convey extent.

- Use rivers as proxies: Downstream features visually represent the glacier’s influence.

- Neutral conditions work: Overcast light preserves surface texture without glare.

- Minimal foregrounds: Snow and ice read best without visual clutter.

- Context frames: Include surrounding highlands to anchor the glacier spatially.