Set on the western edge of Vatnajökull National Park, Langisjór is a long, high-altitude lake shaped by Iceland’s volcanic architecture and sustained by a harsh, highland hydrological regime. Its isolation is part of its meaning: the journey filters the experience, and what remains is clarity—of water, of landform, and of the processes that built both.

The location of Langisjór highland lake

Latitude

64.1194

Longitude

-18.4185

Langisjór highland lake

Langisjór sits deep in the southern Highlands, far from built infrastructure and close enough to Vatnajökull’s margins that the wider landscape feels glacial even when ice is not immediately visible. The lake is commonly described as about 20 km long and up to 2 km wide, with a surface area of roughly 26–27 km², and a maximum depth around 75 m. It lies at approximately 670 m above sea level, which matters: at this elevation, weather systems arrive unsoftened, visibility can collapse quickly, and summer still behaves like a negotiated season rather than a guarantee.

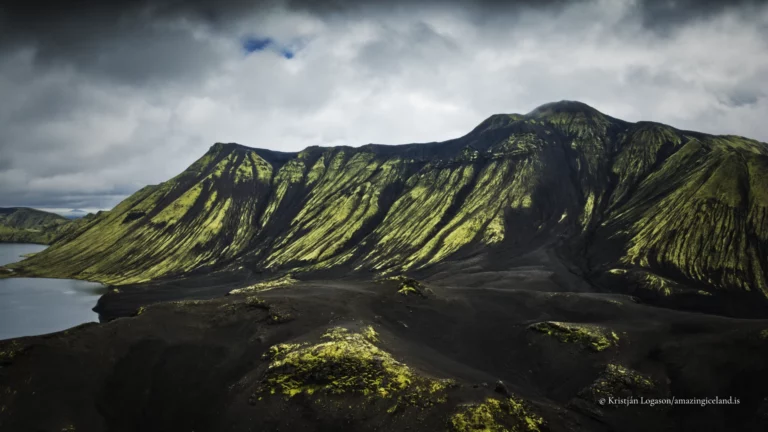

There is a particular kind of authority in a landscape that does not try to be convenient. Langisjór is not positioned for casual access, and that remoteness shapes the visitor’s relationship with it. The lake’s setting—between rugged mountain ridges and volcanic deposits—produces a scene that reads cleanly in geological terms. You are looking at water occupying a long basin in a region defined by volcanism and erosion, with frequent evidence of high-energy surface processes: braided river systems nearby, dark outwash plains, and steep slopes that expose the internal structure of the terrain.

From a physical geography standpoint, Langisjór is valuable precisely because it is simple in plan and complex in context. The lake’s elongation, its altitude, and its confinement between highland ridges encourage a kind of observational discipline. Even without instruments, you can read wind direction across the surface, see turbidity shifts where inflows enter, and watch weather move along the ridgelines in ways that coastal Iceland rarely allows. This is a site where the atmosphere becomes part of the subject, not just the backdrop.

Ecologically, the margins are sparse. The Highlands do not offer lushness; they offer adaptation. Vegetation is limited and slow-growing, and many surfaces are unstable—sand, ash, tephra, and fractured volcanic rock. That constraint creates the lake’s signature palette: blue water, black ground, and muted mountain tones that change with light more than with color. The result is not decorative; it is diagnostic. It tells you what kind of land you are in.

Langisjór is formally presented as part of the Eldgjá & Langisjór area within Vatnajökull National Park. That framing matters because it situates the lake inside a protected landscape whose management priorities include both conservation and controlled access. In practical terms, it explains why the region remains relatively undeveloped—no services at the lake in the way visitors might expect elsewhere, limited signage, and a strong emphasis on staying within established tracks and trails where they exist.

Approach routes typically involve Icelandic F-roads, and Langisjór is most often reached via F235, which branches from F208. The journey requires a capable 4×4 and conditions are seasonal, with access generally limited to the summer period when these highland roads are open. River crossings may be involved depending on approach direction and seasonal melt, and the difference between “possible” and “advisable” is often decided on the day, not on the map.

This is where Langisjór becomes more than a destination name: it becomes an exercise in judgment. Highland travel in Iceland is an applied skill, not a passive commute. Track conditions shift, rivers change character, and weather can compress time. The lake’s isolation amplifies the importance of self-sufficiency and conservative decision-making—especially because the reward is not a single viewpoint that must be “achieved,” but a landscape that benefits from time on site.

And that is the key interpretive adjustment: Langisjór is not best experienced as a photograph you arrive to collect. It is best experienced as a setting you enter—walking its margins, letting scale settle in, and observing how the lake holds light differently from the surrounding black surfaces. In calm conditions, the water can appear unnaturally saturated, almost mineral in tone. In wind, the surface becomes a textured plane and the lake’s color deepens, while the soundscape shifts from silence to constant movement.

One of the most academically and visually productive ways to understand Langisjór is to pair it with the nearby mountain Sveinstindur, widely regarded as a premier viewpoint over the lake. Vatnajökull National Park describes a marked trail to the summit of Sveinstindur at 1,089 m a.s.l., characterizing the hike as steep and challenging, with an estimated 2–3 hours and roughly 400 m elevation gain from the starting area. This is not “add-on content”; it is the clearest way to read the lake as a landform rather than as a shoreline.

From above, Langisjór reveals its true geometry: a long basin positioned between ridges, with the surrounding terrain reading as layered and structurally controlled. The lake becomes a line in the landscape rather than a surface detail. On clear days, the larger system becomes visible—glaciers in the distance, volcanic plains, and the sense that the Highlands are less a region than an exposed interior.

This relationship between lake and viewpoint is also where environmental ethics become unavoidable. The Highlands are fragile. Paths may be faint, surfaces may look durable when they are not, and off-track driving is not simply discouraged—it is actively damaging in environments where recovery is measured in decades. The best practice here is not complicated: stay on established roads, use marked trails where available, and treat the land as slow to heal because it is.

Langisjór also asks for a different tempo. Many Icelandic sites are designed around immediacy: park, walk a short loop, leave. Langisjór is the opposite. Its value emerges in incremental detail—changes in cloud density, the way wind pulls texture across the water, the gradual recognition of how empty “empty” can be when a landscape is truly interior.

That emptiness is not lack. It is context. It makes minor elements meaningful: a single ridge line, a thin stream entering the lake, the subtle tonal difference between fresh ash and older, stabilized ground. For your writing style, this is an advantage. Langisjór supports the kind of narrative that respects process: the lake as evidence, the surrounding terrain as explanation, the journey as part of the methodology.

Finally, Langisjór is a reminder that Iceland’s interior is not an extension of the ring road experience—it is a different category of landscape. The lake’s measurements and coordinates can be listed, but that information is only the administrative layer. The real content is the interaction between water and volcanic ground, between visibility and weather, and between access and restraint.

If there is a single principle that defines Langisjór as a destination, it is this: the lake does not ask to be conquered. It asks to be read. And when you read it properly—shoreline first, then viewpoint, then the broader system—the Highlands stop being “remote” and become simply what they are: Iceland’s core processes exposed.

Interesting facts:

- Langisjór is approximately 20 km long, up to 2 km wide, with a surface area around 26–27 km².

- The lake reaches roughly 75 m depth at its deepest point and sits near 670 m elevation.

- Langisjór is described as part of the Eldgjá & Langisjór area within Vatnajökull National Park.

- Sveinstindur is a principal viewpoint: the park notes a summit height of 1,089 m a.s.l. with a steep trail and 2–3 hour hiking estimate.

- Access is typically via F208 + F235, and travel guidance emphasizes summer-only road access and the potential for river crossings.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Treat color as geology, not editing. The blue water against black volcanic ground is real, but it is light-dependent. Overcast gives control; broken cloud gives drama—both work, but they produce different “truths.”

- Build sequences, not single frames. Start with shoreline detail (water texture, volcanic sand), then mid-scale compositions (ridges framing the lake), then end with a viewpoint frame (Sveinstindur) to make the landscape legible as a system.

- Use wind intentionally. Calm water supports reflection and clean color fields. Wind creates texture and scale cues—especially useful when the terrain is visually minimal.

- Avoid foreground damage. Moss and fragile ground can be present even where it looks “empty.” Keep to durable surfaces and existing paths where possible; your best images will not be worth avoidable scars.

- Compose for isolation. Here, absence is a compositional tool. Let negative space carry meaning—wide frames that would feel “too empty” elsewhere often become the point at Langisjór.