Landmannalaugar is one of Iceland’s most geologically expressive landscapes: a highland basin of rhyolite mountains, lava fields, geothermal activity, and braided rivers within the Fjallabak Nature Reserve. Located at the northern end of F208, the area is internationally known for its colour-rich mountains and natural hot spring, but its deeper significance lies in how clearly it reveals the interaction between volcanism, tectonics, water, and time.

The location of Landmannalaugar

Latitude

64.0431

Longitude

-19.2696

Landmannalaugar

Landmannalaugar sits within the Torfajökull volcanic system, one of Iceland’s most complex and compositionally diverse volcanic regions. Unlike much of Iceland, which is dominated by basaltic volcanism, Torfajökull is characterised by rhyolite, a silica-rich volcanic rock formed during explosive eruptions. This difference in composition is fundamental to understanding both the appearance and behaviour of the landscape.

Rhyolite weathers more rapidly than basalt and produces a broad colour range as minerals oxidise and alter. The result is a terrain marked by yellows, greens, reds, greys, and pale blues—colours that shift with moisture, light, and seasonal change. In Landmannalaugar, these colours are not surface decoration; they are a direct expression of chemical composition and hydrothermal alteration.

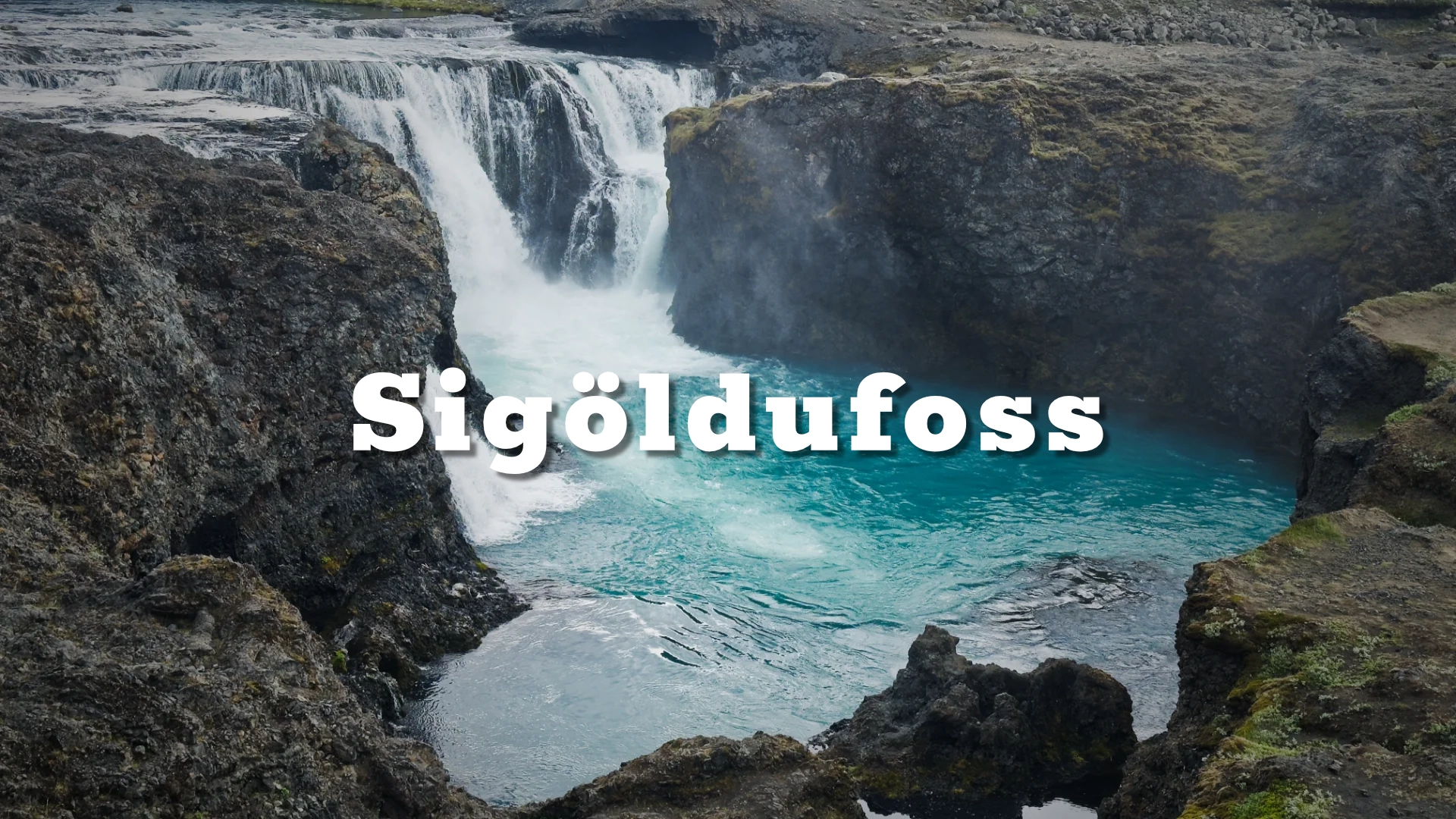

The area has been shaped by repeated eruptions, lava flows, and geothermal processes over tens of thousands of years. One of the most influential events in the modern landscape was the 1477 Veiðivötn eruption, which sent extensive lava flows through the region. The dark Laugahraun lava field, which borders Landmannalaugar, dates from this eruption and provides a stark contrast to the softer, colourful rhyolite mountains rising beside it.

This juxtaposition—young basaltic lava against older, altered rhyolite—is one of Landmannalaugar’s defining characteristics. It allows visitors to read volcanic history directly in the terrain, observing how different magma types produce fundamentally different landforms and textures within a single, relatively compact area.

Geothermal activity, water, and ecological limits

Landmannalaugar’s geothermal features are not extreme by Icelandic standards, but they are unusually accessible and visually integrated into the landscape. Steam vents, warm ground, and sulphur-stained slopes appear throughout the area, particularly around mountains such as Brennisteinsalda, whose name (“Sulphur Wave”) reflects the mineral activity visible on its flanks.

At the base of the lava field lies the natural hot spring that has made Landmannalaugar famous. The warm water emerges where geothermal heat interacts with shallow groundwater, creating a pool where hot and cold streams mix. The location of this spring—at the boundary between lava and sediment—highlights the importance of permeability and fracture systems in controlling water movement in volcanic terrain.

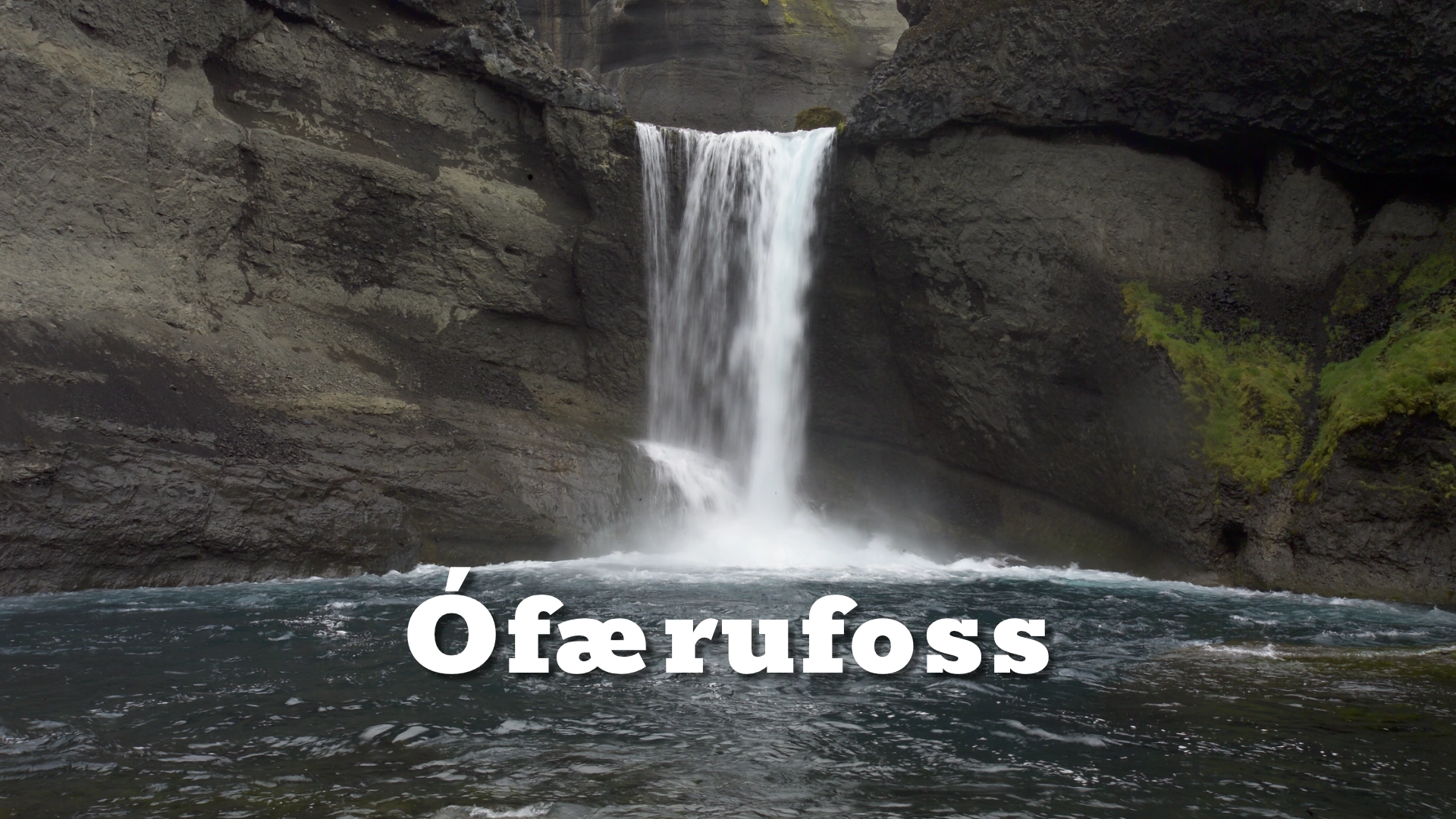

Surface water plays a central role in shaping Landmannalaugar despite the area’s elevation and exposure. Rivers such as the Jökulgilskvísl braid through the basin, transporting sediment and reshaping channels after heavy rain or snowmelt. These rivers are dynamic rather than fixed, and their shifting courses reinforce the sense that Landmannalaugar is an active system rather than a static landscape.

Ecologically, the area exists near the limits of what can persist. Vegetation is sparse and dominated by mosses, lichens, and low alpine plants adapted to short growing seasons, unstable ground, and mineral-rich soils. Where geothermal warmth slightly moderates conditions, plant life can be more concentrated, but even these pockets remain fragile.

This ecological restraint is an essential part of Landmannalaugar’s character. The absence of dense vegetation keeps geological structures exposed and legible, allowing erosion patterns, lava textures, and mineral staining to remain visible. It also means the landscape is highly sensitive to disturbance, a fact that underpins the area’s protected status.

Human presence, access, and experiential meaning

Human interaction with Landmannalaugar has historically been seasonal and utilitarian. The name itself refers to the “people’s pools,” suggesting long-standing awareness of the warm springs as a practical resource for travellers moving through the interior. Despite this history, permanent settlement was never viable, and the area remained a place of passage rather than habitation.

Modern access is primarily via F208 and F225, mountain roads that are typically open only during the summer months. River crossings, weather variability, and rapidly changing conditions remain part of the experience, reinforcing Landmannalaugar’s position firmly within the highlands rather than the lowland tourist network. Facilities are limited to basic huts, trails, and designated camping areas, designed to concentrate use rather than spread impact.

Landmannalaugar is also the northern terminus of the Laugavegur trail, one of Iceland’s best-known long-distance hiking routes. While this brings seasonal crowding, it also situates Landmannalaugar as a gateway rather than an endpoint—a place where journeys begin or conclude, and where the broader logic of the highlands becomes apparent.

Experientially, Landmannalaugar differs from many iconic Icelandic sites. It does not rely on a single focal feature. Instead, its impact emerges cumulatively: the shift from black lava to coloured slopes, the smell of sulphur in damp air, the sound of wind across open ground, and the contrast between cold rivers and warm water. These elements work together to create a landscape that rewards time and attention rather than rapid consumption.

Landmannalaugar functions as a field laboratory. Volcanology, geomorphology, hydrology, and ecology are all visible at human scale. From a destination perspective, it offers something rarer: a sense of coherence. Everything present—rock, water, colour, and space—belongs unmistakably to the same system.

Landmannalaugar is not just visually distinctive; it is explanatory. It shows how Iceland works.

Interesting facts:

- Rhyolite dominance: Landmannalaugar is one of the largest rhyolite areas in Iceland.

- 1477 eruption: The Laugahraun lava field dates from the Veiðivötn eruption.

- Geothermal mixing: The hot spring forms where warm geothermal water meets cold surface flow.

- Highland gateway: It marks the northern end of the Laugavegur hiking trail.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Work in layers: Combine lava foregrounds, mid-ground rivers, and rhyolite mountains.

- Soft light excels: Overcast or broken cloud reveals colour variation without harsh contrast.

- Avoid oversaturation: The landscape is already colour-rich; restraint preserves realism.

- Human scale sparingly: Small figures help communicate scale but should not dominate.

- Weather patience: Rapid changes often produce the most nuanced light.