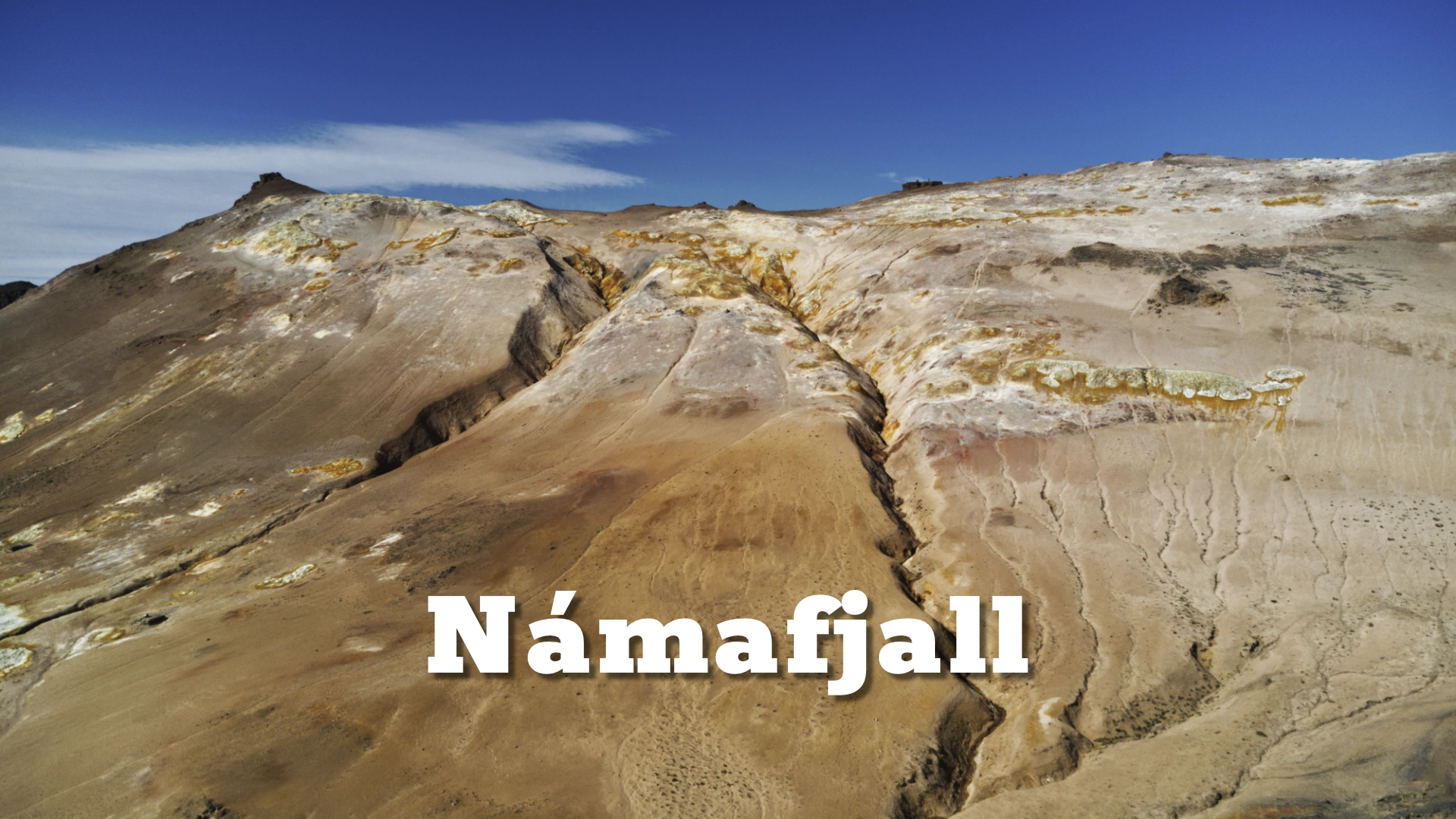

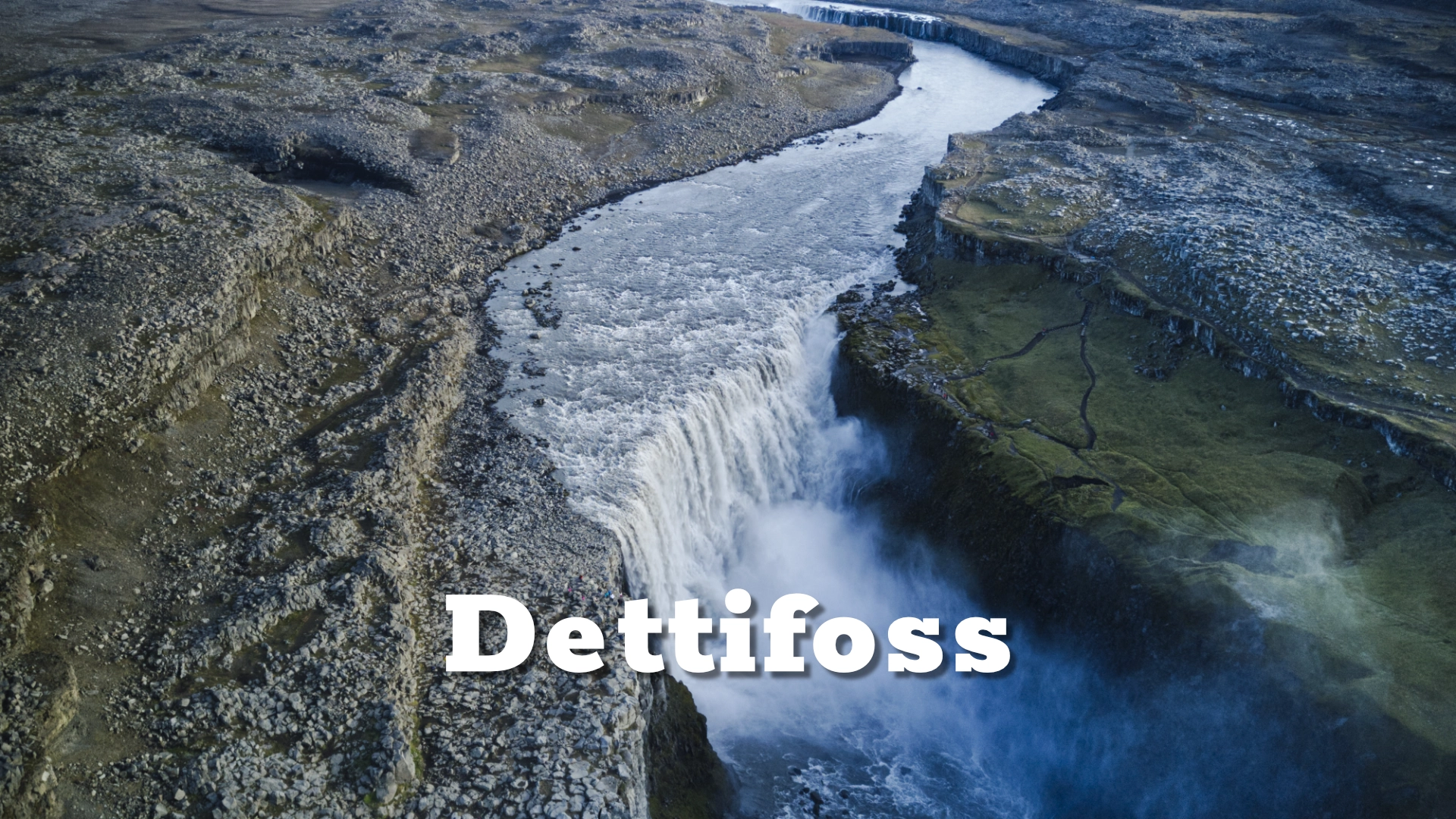

North of Lake Mývatn, the Krafla volcanic system compresses Iceland’s big story—plate divergence, magma movement, hydrothermal circulation—into a landscape you can traverse on foot. The power station is a working endpoint of that geology: heat becomes electricity, while the surrounding terrain (Viti crater, Leirhnjúkur, and nearby geothermal fields) offers an unusually legible cross-section of volcanic processes in action.

The location of Krafla power station

Latitude

65.7112

Longitude

-16.7736

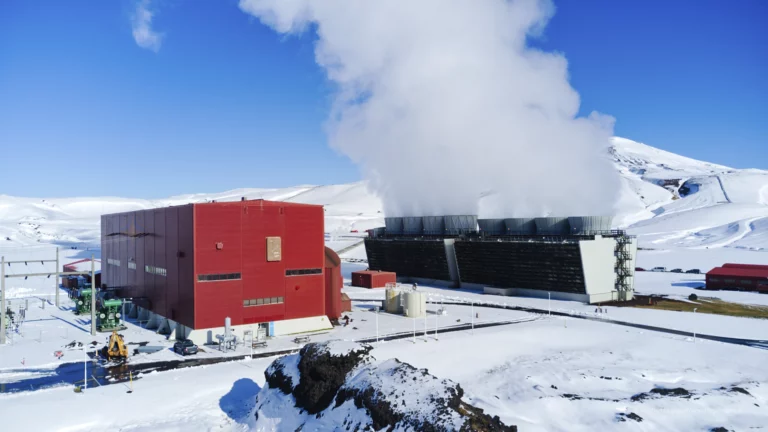

Krafla power station

Krafla is not a single cone volcano in the popular sense; it is a central volcano with a caldera and an associated fissure swarm—part of Iceland’s active rift environment where the Mid-Atlantic Ridge comes onshore. This matters because the landscape is shaped less by one dramatic summit and more by long, linear fractures that open, inject magma, and reorganize the subsurface plumbing over time. The result is a broad, geologically young terrain of lava fields, crater rows, and geothermal alteration zones that read like a map of processes rather than a postcard of one peak.

The modern identity of Krafla is inseparable from the “Krafla Fires” (1975–1984), a prolonged rifting episode with repeated deformation events and multiple eruptions. In plain terms, the ground inflated and deflated as magma moved, and fissures opened episodically—sometimes producing lava, sometimes only reshaping stress and fluid pathways. This was not only a major natural event; it also became a rare case study where scientists could observe rifting dynamics in real time and where infrastructure projects had to adapt to an active volcanic system rather than a dormant one.

For visitors, the geological consequences are immediate. The terrain around Leirhnjúkur and the broader Krafla area includes fresh-looking basaltic lava, fractured surfaces, and zones where the ground is stained by sulfur and iron compounds from geothermal gases. Even without technical vocabulary, you feel the logic: heat is close to the surface; water circulates, flashes to steam, and vents; and the crust is mechanically stressed by plate motion and magma intrusion. This is why Krafla can look “otherworldly” without any exaggeration—its surface is literally being rewritten by subsurface physics and chemistry.

Krafla Power Station—geothermal engineering in an active volcanic field

Krafla Power Station is a geothermal power facility that converts high-temperature hydrothermal energy into electricity. In operational terms, production wells tap steam (and hot fluids) from depth, separators and gathering systems manage the two-phase flow, and turbines convert steam energy to mechanical rotation and then electrical output. The plant is commonly described as having two 30 MW turbine units for an installed capacity of 60 MW, and it is often reported to generate on the order of ~500 GWh per year (recognizing that annual output varies with reservoir performance and operational constraints).

What makes Krafla academically and practically notable is not merely that it produces renewable electricity, but that it was developed while the volcanic system demonstrated active unrest and eruptive behavior. A major decision to develop the field was made in the 1970s, and the subsequent eruptive period affected construction and reservoir chemistry—especially through increases in corrosive volcanic gases in parts of the field. The history reads like applied volcanology: siting decisions, well strategy, and surface design all had to account for risk, fluid chemistry, and the realities of operating industrial systems in a corrosive, dynamic environment.

The commissioning and ramp-up history illustrates this adaptive pathway. A key technical account describes early operation with a single unit and gradual scale-up, with the station reaching full 60 MW only after the second turbine was ultimately brought into service; it also notes how operational changes—such as centralized separation and improved steam handling—were implemented to improve reliability and reduce hazards such as noise and problematic steam blowouts near visitor-accessible areas. In other words, Krafla is not only a power plant; it is an evolving system of engineering responses to a difficult geothermal field.

Experiencing the area—Viti, lava fields, and responsible access

The visitor experience around Krafla is best understood as a cluster rather than a single stop. The power station area is the most explicit marker of human use, but the surrounding volcanic terrain—especially Viti crater and the lava/geothermal zones near Leirhnjúkur—provides the interpretive context that makes the station meaningful. Viti (“hell” in Icelandic usage) is an explosion crater associated with historic eruptive activity in the Krafla system and is now known for its vividly colored crater lake when conditions align.

Access conditions, however, are not a footnote here; they are part of the ethics of visiting. The ground can be unstable, geothermal areas can be scalding, and gases may accumulate in low wind conditions. Trails and marked paths exist for good reasons: they reduce both personal risk and cumulative landscape damage. In the Krafla region, the visual temptation is to “just step off” for a cleaner composition—yet that is exactly how fragile surfaces break, and how people get burned in thin-crust geothermal zones. Treat the area like a living field site, not a film set.

From a practical travel perspective, Krafla is typically approached from the Mývatn area, with key features reached by short drives and short-to-moderate walks depending on your route. Seasonal access can change—especially outside summer—so a responsible itinerary assumes variability and prioritizes safe conditions over rigid plans.

Conceptually, this is where Krafla becomes unusually strong as a destination narrative: it allows you to explain Iceland’s geothermal identity with intellectual honesty. You can stand near a working plant that depends on subsurface heat, then look outward at the caldera terrain that produces that heat. In one compact area, the visitor can connect rifting, volcanism, hydrothermal systems, and energy infrastructure—without needing to overstate anything. The landscape does the explaining, provided we give it space and treat it with the respect of a place still in motion.

Interesting facts:

- The Krafla rifting/volcanic episode known as the Krafla Fires (1975–1984) involved repeated deformation events and multiple eruptions within the volcanic system.

- A technical operational history notes Krafla reached full 60 MW only after the second 30 MW turbine was finally put into full service, following decades of staged development.

- Krafla is widely cited as producing ~500 GWh/year of electricity, illustrating how geothermal plants are often described by both capacity (MW) and annual energy (GWh).

- The area’s geothermal chemistry—including corrosive volcanic gases—has materially influenced well strategy and surface system design over time.

- Viti is commonly interpreted as an explosion crater tied to historic eruptive phases in the Krafla system, later becoming a crater lake and visual focal point for visitors.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Work the story in layers: start with wide frames that include steam plumes and the broader caldera terrain, then tighten into textures—sulfur staining, fractured lava, condensate on metal surfaces—to connect geology and infrastructure visually.

- Use steam as a compositional tool: steam behaves like weather; it can simplify backgrounds, reveal wind direction, and add scale. Shoot short bursts and expect variability frame-to-frame.

- Midday is not a deal-breaker here: in bright light, Viti’s water color and mineral tones can read strongly; in flatter light, the lava textures and steam become the subject.

- Bring a lens cloth and protect gear: fine mineral dust and moisture from vents can accumulate quickly, especially in windy conditions near geothermal features.

- Stay on marked paths even for “the angle”: in Krafla, safety and conservation are not abstract. Thin crust and hot ground are real, and off-trail footprints are long-lived scars.