Located on the Hvítá river and fed by meltwater from Langjökull, Gullfoss is a two-tiered waterfall where scale, sound, and geology converge. Its plunging cascades and deep canyon illustrate the erosive power of glacial rivers, while its preservation story marks a turning point in Iceland’s relationship with natural resources.

The location of Gullfoss waterfall on the Golden circle in Iceland

Latitude

64.3270

Longitude

-20.1218

Gullfoss waterfall on the Golden circle in Iceland

Gullfoss lies in southwest Iceland along the course of the Hvítá river, one of the country’s major glacial rivers. Hvítá originates in Langjökull, Iceland’s second-largest glacier, where seasonal meltwater accumulates across the ice cap before flowing southward through the central highlands. Along this journey, water moves through porous lava fields and volcanic sediments, gradually concentrating into a powerful river system shaped by both ice and fire.

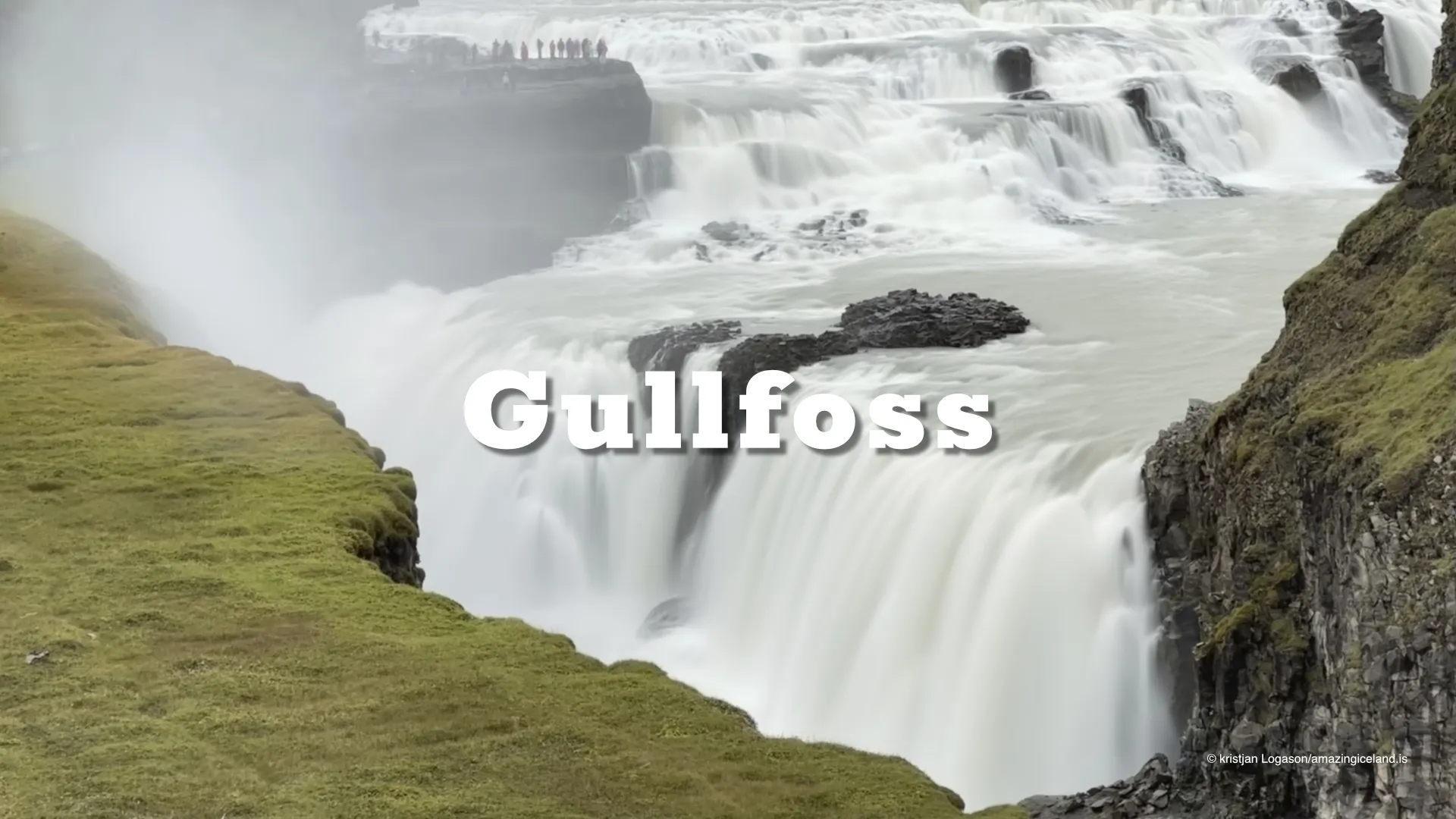

At Gullfoss, this accumulated flow is abruptly confined and redirected. The river drops a total of approximately 33 metres in two distinct stages, disappearing into a narrow canyon carved into layered basalt. The upper fall descends roughly 11 metres, followed by a second plunge of about 21 metres. The canyon itself is approximately 20 metres wide and extends for nearly 2.5 kilometres, creating a dramatic chasm that swallows the river from view when water levels are high.

The physical structure of Gullfoss is a clear demonstration of fluvial erosion acting on volcanic rock. Basalt layers fractured by cooling and tectonic stress provide zones of weakness that glacial rivers exploit over time. The result is not a single vertical drop, but a stepped formation that emphasizes depth rather than height alone. From many viewpoints, the waterfall appears to collapse inward, reinforcing the sensation of scale and force.

The name Gullfoss, meaning “Golden Waterfall,” is often associated with the color and light produced by spray under certain conditions. When low-angle sunlight interacts with suspended droplets, the canyon fills with warm hues that contrast sharply with the dark rock walls. This optical effect, while fleeting, contributes to the waterfall’s reputation and visual identity.

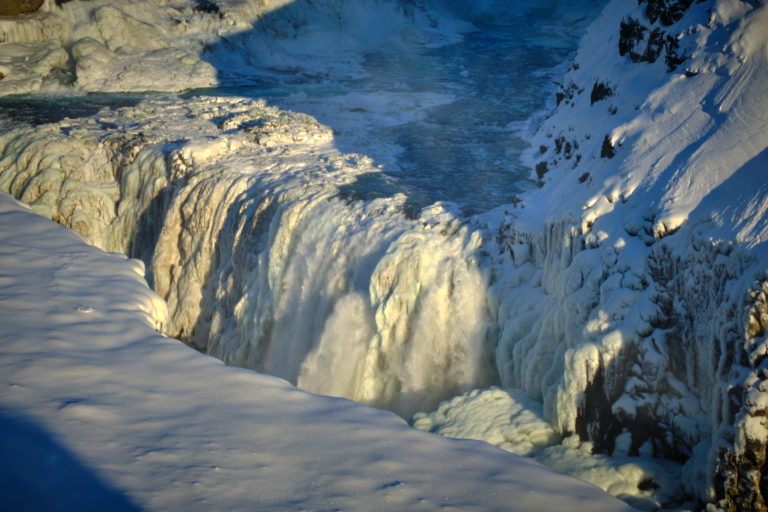

Seasonal variation plays a significant role in how Gullfoss is perceived. During summer, meltwater from Langjökull increases volume, intensifying the waterfall’s power and filling the canyon with dense mist. In winter, reduced flow and freezing conditions introduce structure: ice forms along canyon edges, spray crystallizes, and the waterfall’s geometry becomes more legible. Each season emphasizes different aspects of the same system, reinforcing the idea that Gullfoss is not a static landmark but a responsive environment.

The surrounding landscape supports this reading. Sparse vegetation, exposed lava, and open highland terrain provide little visual distraction. Attention is drawn inward—toward the water, the rock, and the space between them. This clarity is part of Gullfoss’s enduring impact; the site does not rely on scale alone, but on the precision with which geological processes are expressed.

Beyond its geological significance, Gullfoss occupies a central place in Iceland’s cultural and environmental history. In the early 20th century, proposals were made to harness the waterfall for hydroelectric power. At the time, industrial development was often framed as national necessity, and natural features were widely viewed as utilitarian resources.

Opposition to these plans was led by Sigríður Tómasdóttir, daughter of the farmers at Brattholt, the landholding nearest to the falls. Sigríður undertook repeated journeys on foot between Brattholt and Reykjavík, crossing rivers and snow-covered terrain to petition authorities. She confronted government officials directly and became known for declaring that she would throw herself into the waterfall rather than allow its destruction.

Her actions were extraordinary in both persistence and context. At a time when women had limited political influence, Sigríður’s advocacy was public, confrontational, and unwavering. While legal ownership complexities delayed resolution, her efforts brought national attention to the idea that natural landmarks held intrinsic value beyond economic utility.

In 1940, Sigríður’s adopted son acquired Gullfoss, and the waterfall was later sold to the Icelandic state. As environmental discourse matured in Iceland during the mid-20th century, Sigríður Tómasdóttir came to be recognized as a pioneering figure in conservation—often described as Iceland’s first environmental activist.

Formal recognition followed. In 1978, a memorial stone was erected in her honor at Gullfoss, acknowledging her role in safeguarding the site. The following year, in 1979, Gullfoss and its immediate surroundings were officially designated as a protected nature reserve. This designation marked a shift in national policy, signaling that preservation could take precedence over exploitation.

Today, Gullfoss is frequently visited as part of the Golden Circle route, yet its accessibility does not diminish its depth. The infrastructure surrounding the waterfall is designed to manage flow and safety without obscuring the canyon’s raw form. Paths and viewpoints guide movement while preserving sightlines into the gorge.

Gullfoss ultimately stands as both a geological and ethical reference point. It demonstrates the erosive capacity of glacial rivers operating over volcanic terrain, while also embodying a turning point in Iceland’s environmental consciousness. The waterfall’s power is immediate and sensory, but its deeper meaning emerges through context—through understanding where the water comes from, how the canyon formed, and why the site remains intact.

In this way, Gullfoss is more than a waterfall. It is a case study in restraint, persistence, and long-term thinking. Its continued presence reflects a decision made not once, but repeatedly, to value landscape as heritage rather than commodity. That decision continues to shape how Iceland approaches its most defining natural features.

Interesting facts:

- Gullfoss drops a total of 33 metres in two stages: approximately 11 m and 21 m.

- The waterfall is formed by the Hvítá river, which originates in Langjökull glacier.

- The canyon below Gullfoss is around 20 m wide and extends for roughly 2.5 km.

- Gullfoss was nearly developed as a hydroelectric power site in the early 20th century.

- Sigríður Tómasdóttir is widely regarded as Iceland’s first environmental activist.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Work with spray, not against it: Mist is part of the subject; protect your lens and use it to create depth.

- Read the canyon: Compositions that emphasize disappearance rather than drop height convey scale more accurately.

- Seasonal intent: Summer conveys power; winter reveals structure and form. Choose your narrative accordingly.

- Avoid over-wide framing: Excessive width can flatten depth; mid-wide lenses often better communicate the canyon’s geometry.

- Respect conditions: Ice, wind, and spray can change footing quickly—stable positioning matters more than proximity.