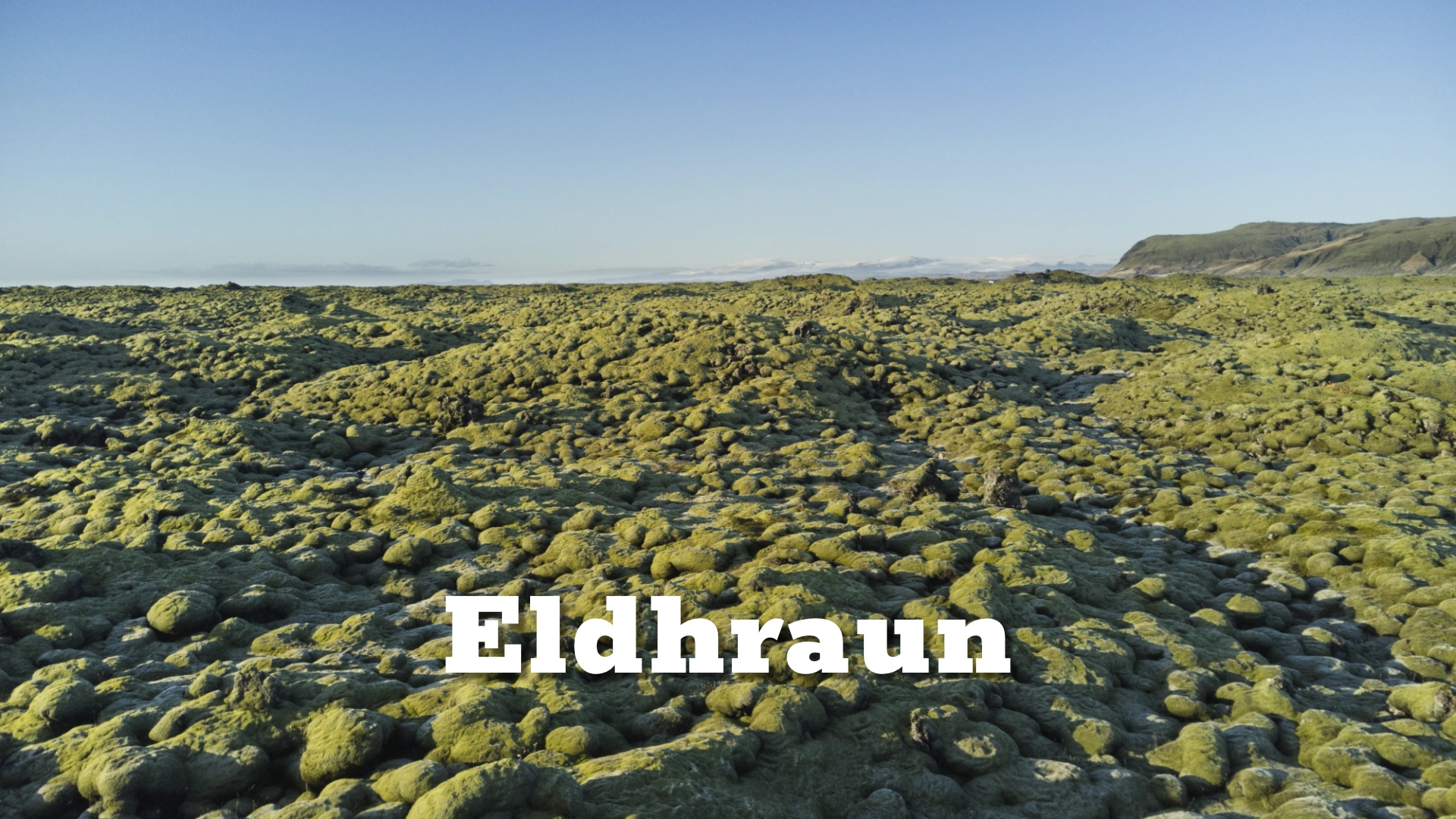

Stretching across the lowlands of South Iceland, near Kirkjubæjarklaustur, Eldhraun is the product of the Laki eruption, one of the most significant volcanic events in recorded history. Today, the lava is softened by moss and silence, but its scale and origin remain legible to those willing to read the landscape carefully.

The location of Eldhraun lava field

63.8256

Latitude

Longitude

-18.1720

Eldhraun lava field

Eldhraun was formed during the 1783–1784 Laki eruption, a fissure eruption associated with the Grímsvötn volcanic system beneath Vatnajökull. Over an eight-month period, lava flowed continuously from a 27-kilometre-long fissure, covering approximately 565 square kilometres of land. The resulting lava field extends from the highland interior toward the coastal lowlands, stopping abruptly against older terrain and natural barriers.

Unlike explosive eruptions that eject material vertically, the Laki event was dominated by effusive basaltic lava flows. These flows advanced slowly but relentlessly, filling valleys, overwhelming vegetation, and permanently altering drainage systems. The lava at Eldhraun is primarily pāhoehoe in character—smooth and ropy when molten—but has since collapsed, fractured, and weathered into a complex surface of ridges, hollows, and pressure folds.

From a geological perspective, Eldhraun is remarkable not only for its size, but for its coherence. It represents a single eruptive system operating over time rather than a patchwork of unrelated events. This unity makes the lava field a reference site for understanding fissure volcanism and large-scale basalt emplacement.

The ecological transformation that followed the eruption was severe and long-lasting. Volcanic gases released during the Laki eruption—including sulfur dioxide and fluorine compounds—had catastrophic consequences for Iceland’s population and livestock. Crop failure, poisoned grazing land, and famine followed, resulting in the loss of a significant portion of the population. Eldhraun is therefore not only a geological feature, but a historical one—directly linked to one of Iceland’s most traumatic periods.

Over time, however, biological processes began to reclaim the lava. The surface of Eldhraun is now dominated by slow-growing moss, particularly Racomitrium lanuginosum. This moss forms thick, sponge-like mats that retain moisture and moderate temperature, creating the first viable substrate for further ecological development. Growth is extremely slow, often measured in millimetres per year, making the ecosystem highly vulnerable to disturbance.

This contrast—between catastrophic origin and fragile recovery—is central to understanding Eldhraun. The lava field does not present as raw or hostile; it presents as subdued and resilient. That restraint is earned, not inherent.

Structurally, Eldhraun is deceptive. Beneath the soft moss surface lies fractured basalt with voids, sharp edges, and unstable cavities. Walking off established paths can cause irreversible damage to both the moss layer and the underlying lava structure. For this reason, access is carefully managed, and visitors are expected to remain strictly on designated routes.

The lava field also plays a role in shaping the surrounding landscape. Its porous structure absorbs meltwater and precipitation, altering surface runoff patterns. Streams often disappear into the lava, re-emerging farther downstream or feeding groundwater systems. This hydrological behavior contrasts sharply with the impermeable cliffs and canyon walls nearby, such as Lómagnúpur, which rise directly from the lava’s edge.

Together, these features create a sharply defined boundary between flow and resistance—horizontal lava spread halted by vertical rock. The meeting of Eldhraun and Lómagnúpur is one of South Iceland’s clearest demonstrations of how different volcanic expressions coexist within a single landscape.

Culturally, Eldhraun occupies a unique position. While it is not directly tied to saga narratives in the way some older landscapes are, its impact is deeply embedded in Icelandic collective memory. The Laki eruption influenced climate across Europe and is cited in historical climatology as a contributing factor to widespread atmospheric disruption in the late 18th century.

In Iceland, Eldhraun stands as a reminder that volcanic events are not abstract geological phenomena—they are lived experiences with social, economic, and demographic consequences. The lava field is therefore both a physical remnant and a memorial landscape, even if that role is understated.

This subdued cultural presence aligns with Eldhraun’s visual character. The field does not dramatize itself. It absorbs sound, flattens perspective, and resists focal points. Meaning emerges through scale and continuity rather than singular features.

Eldhraun ultimately demands a different mode of engagement. It is not a site to be crossed quickly or summarized visually. Its value lies in duration—standing within it long enough to recognize repetition, uniformity, and subtle variation. The lava does not guide the eye; it holds it.

Eldhraun functions as a stabilizing element. It connects explosive volcanic origin to slow ecological recovery, catastrophic history to present-day quiet. It is the landscape equivalent of a long pause.

Interesting facts:

- Eldhraun covers approximately 565 km², making it one of the largest lava fields in the world.

- It was formed during the 1783–1784 Laki eruption, a major fissure eruption.

- Volcanic gases from the eruption caused severe famine and livestock loss in Iceland.

- The lava field is primarily basaltic pāhoehoe lava.

- Moss recovery is extremely slow, making the ecosystem highly fragile.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Avoid wide exaggeration: The field reads best through mid-scale compositions that show repetition.

- Work in overcast light: Diffused conditions preserve moss texture and avoid harsh contrast.

- Respect paths: Footprints permanently damage moss—composition must adapt to access, not vice versa.

- Use vertical anchors: Features like Lómagnúpur or distant ridges help establish scale.

- Minimal color grading: The muted palette is accurate—don’t force saturation.