Located in Northeast Iceland within Vatnajökull National Park, Ásbyrgi lies downstream from Dettifoss and Selfoss along the Jökulsá á Fjöllum river system. Unlike linear river gorges carved gradually over time, Ásbyrgi’s geometry suggests rapid formation—an abrupt event rather than prolonged erosion. It is here that geology, scale, and myth intersect most directly.

The location of Ásbyrgi canyon

Latitude

66.0216

Longitude

-16.5053

Ásbyrgi canyon

Morphology and geological anomaly

Ásbyrgi is approximately 3.5 km long and over 1 km wide, bounded by near-vertical basalt cliffs rising up to 100 metres. Its defining feature—the symmetrical horseshoe shape open toward the south—is highly unusual for fluvial canyons, which typically extend linearly along river courses.

The canyon walls are composed of layered basalt flows, part of the Northern Volcanic Zone, similar in composition to those exposed at Dettifoss and Selfoss. However, the erosional signature here differs markedly. Instead of gradual incision following the river’s path, Ásbyrgi presents a broad, enclosed basin with a flat floor and an isolated central rock formation, Eyjan (“the island”), dividing the canyon into two arms.

This morphology strongly suggests catastrophic flood erosion rather than steady-state river action. The prevailing scientific interpretation holds that Ásbyrgi was carved by one or more massive glacial outburst floods (jökulhlaups) originating from beneath Vatnajökull, likely triggered by subglacial volcanic eruptions. These floods would have released extraordinary volumes of water in a short time, overwhelming the landscape and excavating the canyon rapidly.

Evidence supporting this interpretation includes scoured bedrock, oversized erosional forms relative to modern discharge, and the canyon’s abrupt termination. The current course of the Jökulsá á Fjöllum bypasses Ásbyrgi entirely, reinforcing the conclusion that normal river flow cannot account for its formation.

Catastrophic flooding and landscape timescales

The Jökulsá á Fjöllum river has a long history of extreme flooding events. Geological evidence indicates that some of the largest floods occurred during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, when volcanic activity beneath ice caps repeatedly melted vast volumes of ice in short intervals.

These floods were orders of magnitude larger than anything observed in the historical period. At peak discharge, water volumes may have exceeded hundreds of thousands of cubic metres per second—sufficient to excavate entire canyon systems within days or weeks rather than millennia.

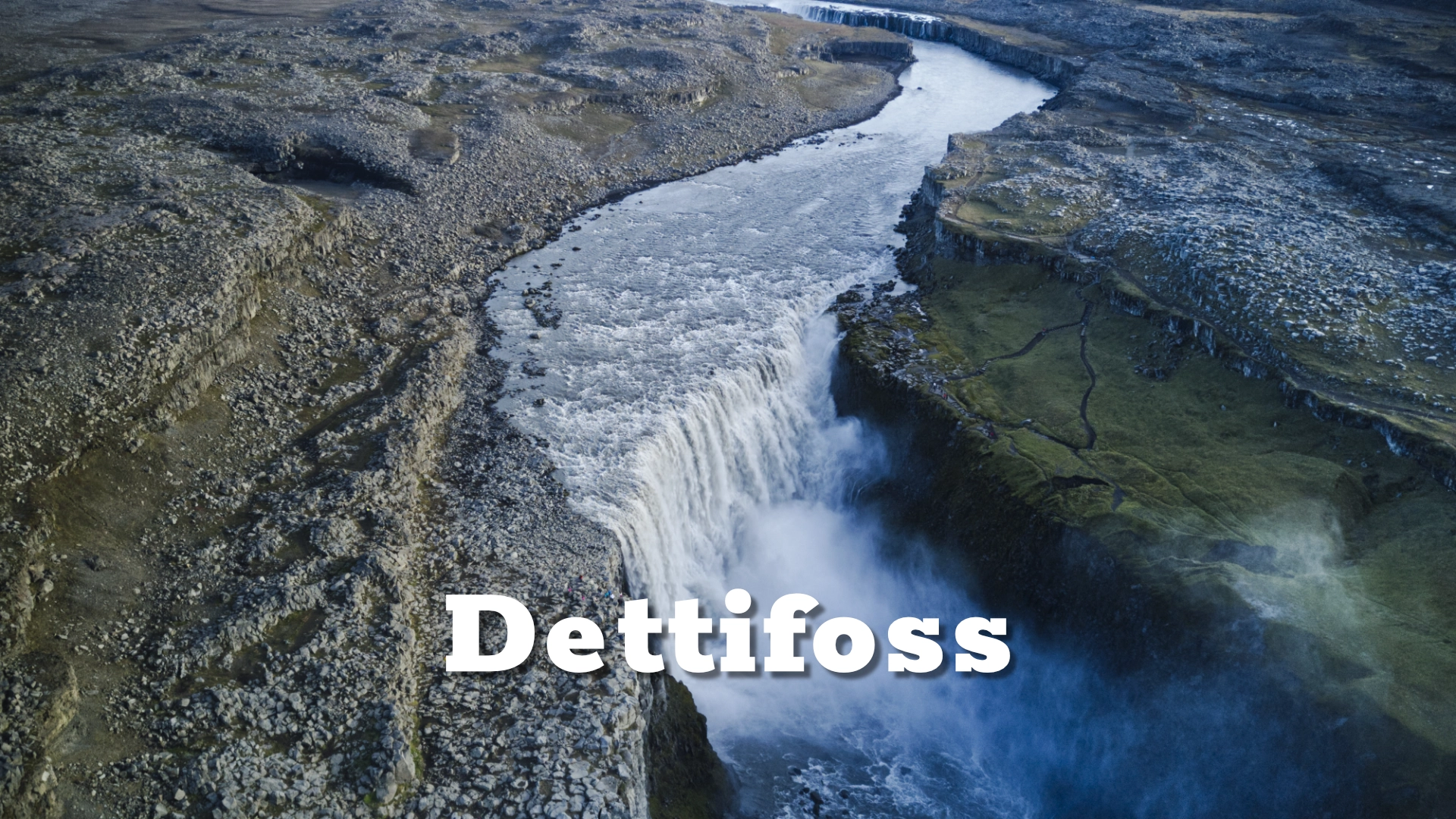

Ásbyrgi represents the terminal expression of this process. Upstream, energy is concentrated vertically at Dettifoss; downstream, it dissipates across broader channels. At Ásbyrgi, floodwaters appear to have expanded laterally, tearing open the basalt plateau and creating a cul-de-sac of erosion.

Ásbyrgi is frequently cited in discussions of megaflood geomorphology, comparable in interpretive importance (though not scale) to features like the Channeled Scablands in North America. It demonstrates that Iceland’s landscapes are not only shaped by gradual processes but punctuated by rare, high-magnitude events.

Ecology and microclimate within the canyon

Despite its violent origin, Ásbyrgi today is one of the most ecologically sheltered environments in Northeast Iceland. The high canyon walls block wind and create a localized microclimate that supports birch woodland, willow, and diverse ground vegetation—an anomaly in an otherwise exposed region.

At the canyon floor lies Botnstjörn, a small pond that acts as a focal point for birdlife and seasonal reflection. The relative calm contrasts sharply with the upstream environment of Dettifoss, reinforcing how geomorphology governs ecological opportunity.

This ecological richness is not incidental. It is a direct consequence of canyon geometry: reduced wind stress, retained moisture, and moderated temperature variation. Ásbyrgi thus illustrates how catastrophic geological events can create long-term biological refugia.

The canyon is also an important nesting area for birds, including cliff-nesting species that take advantage of the vertical walls. Conservation management reflects this sensitivity, with designated paths and restricted zones during breeding seasons.

Mythology, symbolism, and cultural interpretation

Long before scientific explanations emerged, Ásbyrgi was embedded in Icelandic mythology. According to tradition, the canyon was formed by the hoofprint of Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse of Odin, when it touched the Earth. This narrative persists not as quaint folklore but as a meaningful cultural framework for interpreting an otherwise inexplicable landform.

The myth aligns strikingly with physical form: the horseshoe shape, the abrupt walls, and the sense of enclosure all lend themselves naturally to symbolic interpretation. In Icelandic cultural geography, Ásbyrgi functions as a mytho-geological site, where story and structure reinforce one another.

Importantly, modern interpretation does not replace myth with science but allows both to coexist. Visitors encounter Ásbyrgi as a place shaped by unimaginable force and remembered through narrative—a duality that enriches rather than diminishes understanding.

Visiting Ásbyrgi—movement, access, and perspective

Ásbyrgi is accessible via paved and gravel roads from Route 85, making it one of the more approachable major sites in Northeast Iceland. Multiple walking paths lead into the canyon, across the forested floor, and up to viewpoints along the rim.

Experiencing Ásbyrgi effectively requires vertical movement. From the canyon floor, the space feels protected and enclosed; from the rim, its improbable geometry becomes fully legible. Both perspectives are essential, and neither should be rushed.

Trails are well marked, but scale can be deceptive. Distances within the canyon are larger than they appear, and weather conditions can shift rapidly along the rim. Responsible visitation involves allowing time and respecting trail guidance.

Ásbyrgi is often experienced as tranquil, especially when compared to the sonic intensity of Dettifoss. This calm should not obscure its origin. The silence is the aftermath of catastrophe, preserved in basalt.

Ásbyrgi within the Jökulsá á Fjöllum narrative

Within the broader sequence of the Jökulsá á Fjöllum river, Ásbyrgi represents resolution. The river’s energy, built beneath ice and released violently across volcanic plateaus, ultimately dissipates here into form rather than motion.

Seen in sequence—Selfoss, Dettifoss, and Ásbyrgi—the river tells a complete geomorphological story: distribution, concentration, and release. Few places in Iceland allow such a coherent reading of process across distance and scale.

Ásbyrgi is therefore not an isolated wonder but the logical conclusion of one of Iceland’s most powerful river systems.

Interesting facts:

- Ásbyrgi is approximately 3.5 km long and over 1 km wide, with cliffs up to 100 m high.

- The canyon is widely interpreted as having formed through catastrophic glacial outburst floods rather than gradual erosion.

- The modern Jökulsá á Fjöllum river no longer flows through Ásbyrgi, bypassing it entirely.

- In Icelandic mythology, Ásbyrgi is said to be the hoofprint of Sleipnir, Odin’s horse.

- The canyon supports birch woodland, rare in exposed Northeast Iceland due to its sheltered microclimate.

The Locomotive Elite

What do Donald Trump and Iceland’s Locomotive Elite have in common?

Far more than you think.

In The Locomotive Elite, you’ll uncover how a tiny clique in Iceland captured extensive control—of banks, courts, media, and even the central bank.

For decades they ruled, first democratically, then through corruption and in the end through crime, enriching themselves and their cronies while dismantling oversight.

The result?

One of the most spectacular financial collapses in modern history.

Photography tips:

- Climb the rim: aerial perspective is essential to read the horseshoe shape.

- Use scale markers: trees and people emphasize canyon depth effectively.

- Morning and evening light: low sun reveals wall texture and curvature.

- Work both levels: floor-level intimacy contrasts with rim-level abstraction.

- Respect nesting seasons: some areas may be restricted—plan accordingly.